Why Do So Many Genealogical Documents Lead Back to the Mormon Church?

For many writers of history, a perk of the job is visiting libraries, archives, universities and courthouses to dig through dusty boxes and file folders (or, if need be, scrolling through miles of eye-straining microfilm).

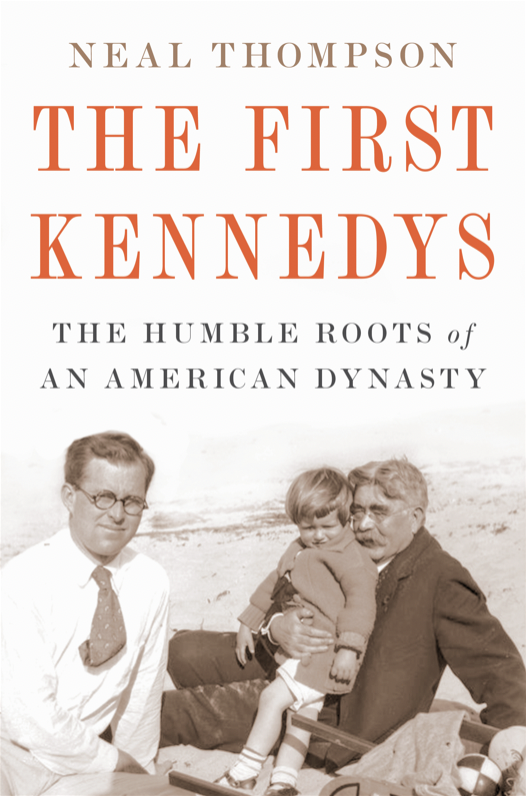

During the final stages of research on a book about the Irish immigrant Kennedys and their first decades in an unwelcoming America, however, the shuttered doors of libraries and archives forced me to rely more heavily on digital collections, which I discovered have come a long way in recent years, thanks in part to the efforts of the Mormon church (more on that below).

I’m not a Boomer and consider myself fairly tech savvy, but the discovery of downloadable riches at online repositories like Ancestry.com, FamilySearch.org, MyHeritage.org, and especially Newspapers.com, along with Archives.gov (the National Archives), Archive.org, Hathi Trust, and the digital offerings of libraries and magazines like Harpers and The Atlantic, rocked me. I felt like a guy from the pre-Internet days who gets handed a Kindle. How many books in there?

Especially at Newspapers.com, I would sit in my attic office and lose hours virtually flipping through the pages of a late 1800s Boston Globe or William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator. I was shocked to find so many pages of scanned century-old newsprint at my fingertips, even if some of the headlines were depressingly familiar—immigration restrictions, voting rights proposals, claims of stolen elections, antisemitism, racism…

As a reporter trained in the late 1980s, I retain some old-school sensibilities. I recall, with fondness and a cold sweat, going to the newspaper morgue during my early reporting days to ask for clips on a given subject. The librarians were always smart, prickly, often bossy and intimidating.

The Church has claimed that its longtime interest in digitizing historical records isn’t some religious plot but an effort to connect people with their past.But online? I was in control. Each service (some free, most requiring a subscription) helped me assemble assorted puzzle pieces. Google searches? A mess, controlled by that mysterious borg, the algorithm. But time spent at Newspapers.com felt comforting and safe. My own private time machine. My Covid bubble. I could turn the page on an 1889 issue of the Boston Globe or flip back to my search results and explore the pages of the Kansas City Star of 1892.

I missed interacting with archivists and librarians, for sure, and missed the thrill of discovering a buried gem and holding century-old documents in my white-gloved hands—like the time I was hunting for a court transcript in a rural Georgia courthouse and found it misplaced atop a file cabinet, gifting me a word-for-word breakdown of a moonshine-related murder trial.

My Covid-era research focused on Irish immigration in the 1800s, when the refugee and first-generation Kennedys were striving to make a life for themselves. It took me down many historic paths: Irish maids and grocers, saloons and liquor sales, airborne illnesses that ravaged the immigrant slums of Boston and New York, violent episodes of anti-immigrant protest, deeply embedded nativism, rioting at the polls, Wide Awake mobs and Know Nothings.

Sadly, I found many 19th-century headlines that echoed the xenophobic chatter of recent years. “A rush of immigrants” and “Undesirable Immigrants Will be Barred at the North” (The Baltimore Sun, March 23, 1900), about an agreement with Canada to prevent Eastern European immigrants arriving in Canadian ports from crossing into the US. “Antisemitic Propagandists are Poisoning the Minds of People through Ford” (The Buffalo News, Nov. 21, 1920), about anti-immigrant articles in Henry Ford’s paper, The Dearborn Independent.

From these and other sources, I learned about Know Nothing gangs that patrolled polls in the 1850s, the Wide Awakes wielding clubs and pitchforks, demanding to see naturalization papers, threatening those who looked or sounded foreign, inciting riots in Cincinnati, New Orleans, St. Louis, and Chicago. I learned about a Baltimore man named Charles Brown gunned down by a Know Nothing thug outside his polling place, leading to an exchange of gunfire that killed five. The Baltimore American bemoaned the “guerilla warfare” tactics that the nativist American Party used to prevent immigrants from voting.

In Louisville, rioters torched a brewery, killing those trapped inside. Drunk on stolen brandy, they raged through the Irish district, Quinn’s Row, setting fires and beating residents, including a priest, who was stoned to death. The Louisville Times described “barbarism which could not be surpassed by the wildest savages.” One woman, running from the flames with an infant in her arms, was “followed by a hard-hearted wretch who . . . put the muzzle of the weapon to the child’s head, fired, and bespattered its brains over its mother’s arms,” said the Louisville Daily Journal, which described men “roasted to death” and roundly scolded the American Party’s “appetite for blood.”

It wasn’t just Newspapers.com—or my fixation on “send them back” and “build a wall” stories—that occupied my research efforts. I also explored digitized copies of obituaries, birth notices, letters to the editor, ads and want ads, legal notices, ships’ passenger lists, citizenship applications. And I was regularly able to find scanned copies of 150-year-old books with surprising ease.

With billions of pages of records online, these and other such sites have become invaluable tools for historians like myself.Let’s say I came across a reference in a Wikipedia footnote to some obscure 19th-century book—A History of East Boston, with Biographical Sketches of its Early Proprietors (1858) or The Story of the Irish in Boston (1889) or the three-volume History of the Archdiocese of Boston in the Various Stages of Its Development (1944). In the past, I’d have to wait weeks to order such books from a used bookseller or through an inter-library loan. Now they’re waiting for me on the web at Archive.org or Hathi Trust or sometimes Google Books. Often, I could find and download a pdf, print and be reading and highlighting within minutes.

Which brings me back to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

A reporter friend once asked me if I felt any guilt for contributing to an enterprise that was allegedly aimed at capturing deceased souls and “baptizing” them into the Mormon church. That lead me to digging into how and why so many genealogical documents and old obits and newspaper articles were so easily within my digital reach, compliments of the Mormons’ efforts.

According to a 2015 Mother Jones article, the Church began collecting genealogical records in the late 1800s and storing them in a bunker known as The Vault. The alleged idea was that church members could use such records to identify and posthumously baptize ancestors, who might join them in the afterlife.

The Church has claimed that its longtime interest in digitizing historical records isn’t some religious plot but an effort to connect people with their past. On the FamilySearch.org website, it explains: “Feelings of family connection can help us overcome the ups and downs of life. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints funds FamilySearch to help people draw strength from their family relationships—past, present, and future.” As a non-religious person, that explanation sounded good enough for me. Mainly I’m just grateful for the resources—which have been a lucrative venture for the Church.

Ancestry.com launched in 1998, created by two Brigham Young University grads; it was followed by MyFamily.com, FamilySearch.org, and Newspapers.com, which was spun off into a separate site in 2012. Ancestry.com was sold to a private equity firm in 2012 (for $1.6 billion), sold again in 2016 ($2.6 billion), then sold to Blackstone in late 2020 (for $4.7 billion).

I’m okay with that. With billions of pages of records online, these and other such sites have become invaluable tools for historians like myself. It’s worth a few hundred dollars a year to be able to log on and within a few clicks find an old newspaper article that a few short years ago would’ve required an inter-library loan microfilm request, a visit to my downtown library, and hours with one of those clunky old microfiche machines. Then again, that ease of access brings with it regular reminders that the past is unnervingly present. (“Infected Refugees Seek Passports to U.S. Warning Issued Against Spread of Disease by Immigrants from Russia,” New York Tribune, March 23, 1922.)

__________________________________

The First Kennedys by Neal Thompson is available via Mariner Books.