What does high immigration mean for the government’s popularity? What data on voting habits tells us

The news from the Office of National Statistics that net migration reached a record high of 606,000 in 2022 is likely to have embarrassed the government, particularly the home secretary, Suella Braverman. For years, successive prime ministers have promised reductions in net migration, but without much success in delivering them.

But do these numbers actually mean anything for a government hoping to win an election?

The public is divided in its attitudes to immigration in Britain. That said, more people have a favourable view of immigration than have an unfavourable view. This was apparent in a recent survey conducted by Ipsos on behalf of the think tank British Future. The survey showed that 46% of respondents had a positive view of immigration and 29% had a negative view, with 18% not sure about the issue. The remaining 7% said they didn’t know how they felt.

In our recent book my colleagues and I modelled the determinants of voting behaviour in the 2019 general election and found that immigration played no direct role in influencing the vote. Rather, the election was dominated by the popularity of the party leaders, party loyalty, the state of the economy and also the Brexit issue.

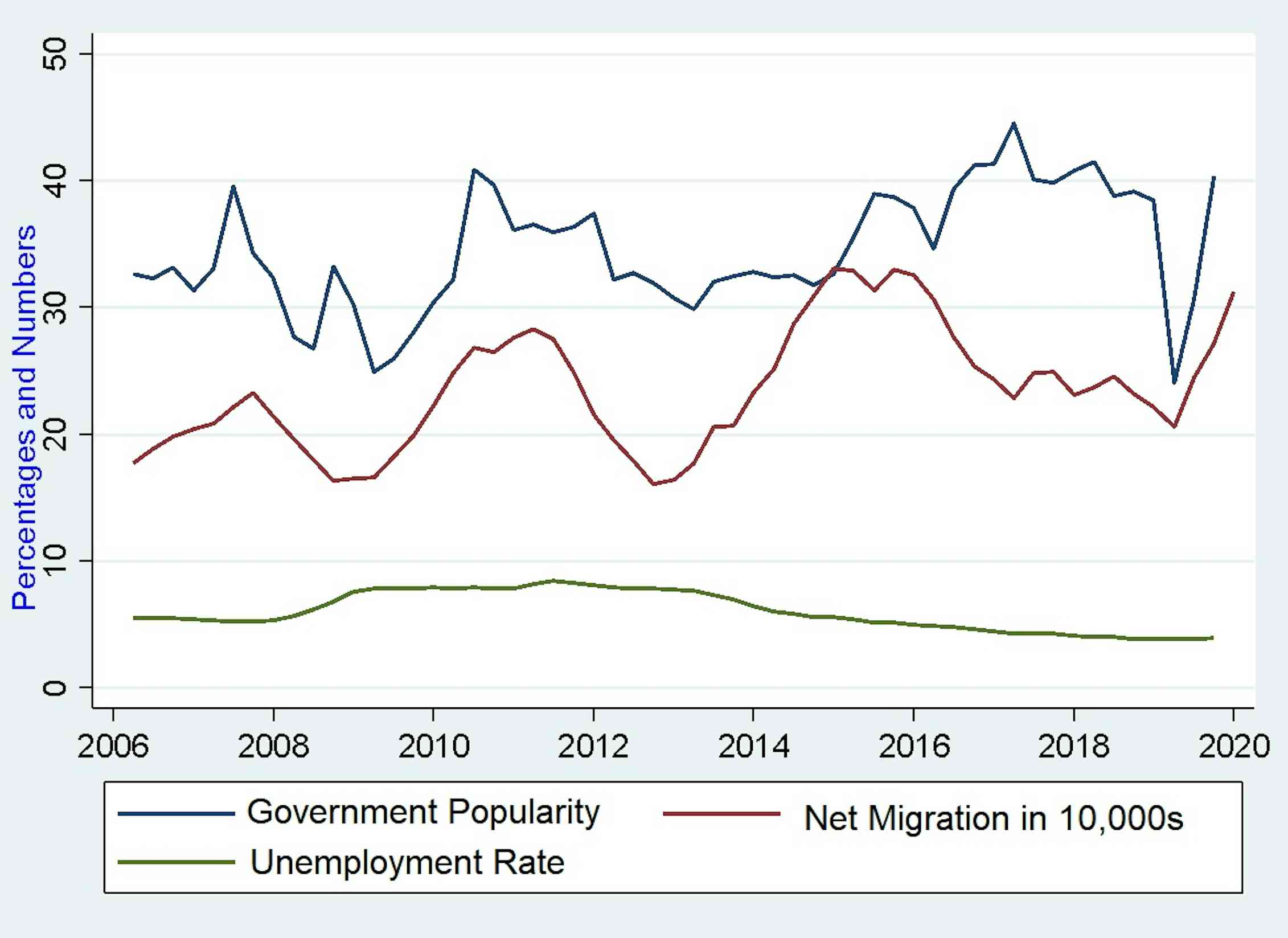

If we look at the actual net migration numbers over time and compare it with support for the governing party, the relationship between them is positive, not negative. As the chart below shows, as the number of immigrants increases, so do voting intentions for the governing party. The correlation between the two is fairly strong (r = 0.49), and it applies to both Labour and Conservative governments.

Voting intentions for the government, net migration and the unemployment rate in Britain (quarterly data 2006-2019)

We know that very high rates of immigration put a considerable strain on public services such as the NHS, education and housing. In addition, all the political parties and the public worry about it – though public concern about immigration has declined in recent years.

One clue to the puzzle of the positive link between immigration and government support lies in the state of the economy, in this case measured by the rate of unemployment. There is a negative relationship between unemployment and net migration into Britain (r = -0.29). In other words, as immigration increases over time, unemployment declines.

This is not surprising, since when Britain was a member of the European Union many workers came from the EU, particularly from eastern Europe, attracted by plentiful jobs and high pay compared with their home countries. We have recently seen the consequences for the UK job market of these workers leaving Britain after Brexit. Many positions are currently not being filled, causing shortages in the shops and adding to inflation.

The chart shows that unemployment rose after the start of the global financial crisis in 2008. By 2010, when the worse effects were over, net migration rapidly increased. But the government did not lose support as a result, and its popularity started to increase in 2014. The effects of the Brexit referendum are apparent in the chart as well, since net migration fell rather dramatically after the vote to leave in 2016. But during this period, government popularity did not really increase.

Several studies have examined the effects of immigration on employment and the wages of existing workers, and most have found either small or no effects. The Migration Advisory Committee, an independent body which advises government on immigration policies, reviewed the results of recent studies in 2018, and concluded that immigration did not lead existing workers to lose their jobs, and had little impact on wages.

People may be increasingly relaxed about legal immigration partly because it does not have damaging economic effects. But they are not as relaxed about illegal immigration.

It is important to recognise that the issue of immigration overall is different from that of people arriving illegally, although they are often conflated in public conversations. A recent YouGov poll showed that the public has a more negative attitude to asylum seekers crossing the channel than towards immigration in general.

Asylum seekers who arrive on small boats are often perceived as a threat to the security of the country and so invoke fear and anxiety among voters. There is a wealth of academic literature showing that negative emotions such as fear, anger and anxiety have powerful impacts on political attitudes and contribute to the growth in support for populism.

The upshot is that if incumbent parties want to be reelected they should focus on curbing irregular arrivals, while at the same time stressing the cultural and economic benefits of immigration. The government is struggling to address this, and their repeated failure to deal with the issue is hurting their credibility.

Labour will inherit this issue if elected next year, and may have an opportunity to reset policies in this area. But without a credible plan to deal with illegal migration, they will face the same problem as the current government.

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.