Tricks, Tension, Surface, Suspense

Paris, 1954. Jules Dassin—blacklisted in Hollywood for his Communist affiliations—hadn’t worked on a film set in four years. He wandered the mist-shrouded city streets scouting locations for a film based on a crime novel titled Rififi. He hated the book, in part for its racism, but needed the job. The adaptation was to be shot on a $200,000 budget with an underpaid crew and no star power; in fact, Dassin himself would decide to play a central role. Dassin’s character, César, is eventually killed by Tony—a member of his own band of thieves—for naming names, in an allegorical comeuppance fantasy aimed at Dassin’s enemies in the entertainment industry: those former colleagues who, in his words, “put their careers before honor” by ratting out Communists. Tony is a recently released jewel thief who, as another figuration of the effects of Dassin’s blacklisting, looks unkempt, ill, and nearly unable to breathe until he’s recruited by his friend Jo to rob a highly secure jewelry shop. This seemingly impossible task is taken on by a multilingual team assembled from Paris’s criminal demimonde, self-consciously staging the international crew’s own predicament in making the film.

Rififi is most famous for its nearly silent half-hour heist sequence, a triumph of restrained suspense that not only influenced countless techno-thrillers to follow, but also served as a practical how-to that was copied by actual criminals internationally; the film was temporarily banned in Paris, Finland, and Mexico. The crime is carefully planned and rehearsed in detail, grounding the scheme within our physical universe, and the heist that follows unfolds procedurally. The thieves pervert the functions of everyday objects around them through extraordinary yet naturalistic methods: they access the jewelry store by boring through its ceiling, then slide an upturned umbrella through this pilot hole to keep debris from setting off the highly sensitive security alarm below—which, once downstairs, they immobilize with fire extinguisher foam.

But Rififi also has a more classically dramatic narrative appeal; its elaborate, snaking plot and tragic arc earned it widespread acclaim upon its release. While the heist sequence is the centerpiece, the emotional climax comes when tough-guy gangster ethics are pushed to their limits through the criminals’ intimate relationships. Those heart-wrenching plot points include: Tony reuniting with his girlfriend (provoking the ire of a gang boss), the discovery of a stolen ring (that César had given to his lover), and Jo’s child being held ransom by the gang in exchange for the jewels. These intertwined human dynamics all have fatal consequences, situating the film, which Dassin insisted on shooting only on rainy days, in the legacy of post-neorealist film noir.

Ten years later, though still living in Europe, Dassin, who by then had found renewed success among American audiences, was tapped by Filmways to direct a film—to be called Topkapi—based on Eric Ambler’s jewel heist novel The Light of Day. This film, his first caper since he set the bar for the genre with Rififi, would be received with far less critical acclaim. While it’s true that Topkapi is no Rififi, it was never intended to be; in fact, much of Topkapi’s charm comes via Dassin’s cheeky, self-parodic inversions of the earlier film’s brutality.

Around the same time, Italian fringe filmmaker Mario Bava, who specialized in low-budget horror movies, was approached by the producer Dino De Laurentiis (backed by Paramount) to make another heist adaptation, this one of the Italian comic Diabolik. Like Topkapi, Bava’s Danger: Diabolik, despite its predestination as a commercial caper of extravagant superficiality, is a masterpiece of Romantic irony—a kind of self-reflexivity or self-consciousness of the work’s fictions made manifest. It alludes, repeatedly, to the systems of artifice that produce its world.

Left: Topkapi (1964) by Jules Dassin. The introductory title sequence unfurls with a prismatic display of colors, as though our vision is situated within a jewel. Right: Danger: Diabolik (1968) by Mario Bava. Following Diabolik’s smoke-shrouded opening heist, the image begins to rotate rapidly, dissolving into spinning gem-like abstraction for the introductory credit sequence.

In both films, emeralds motivate skin-deep characters, emotionally flattened caricatures of sixties excess. It’s clear they don’t need the gems, like so many of the thieves in noir films of the previous decade, so no “fence” is required to convert the fetish objects into capital. They aren’t down-on-their-luck crooks, so viewers aren’t positioned as political subjects, called upon to identify with the existential stakes of have-nots. The female protagonist of each film already has a lot, but wants more. The moment she lays eyes on the precious gemstones, she can’t seem to live without them. Neither woman’s gaze looks beyond the surfaces of the gems for their inherent value, as liquid assets geared towards circulation; they’re simply objects of desire to be acquired, cherished, fondled, and displayed.

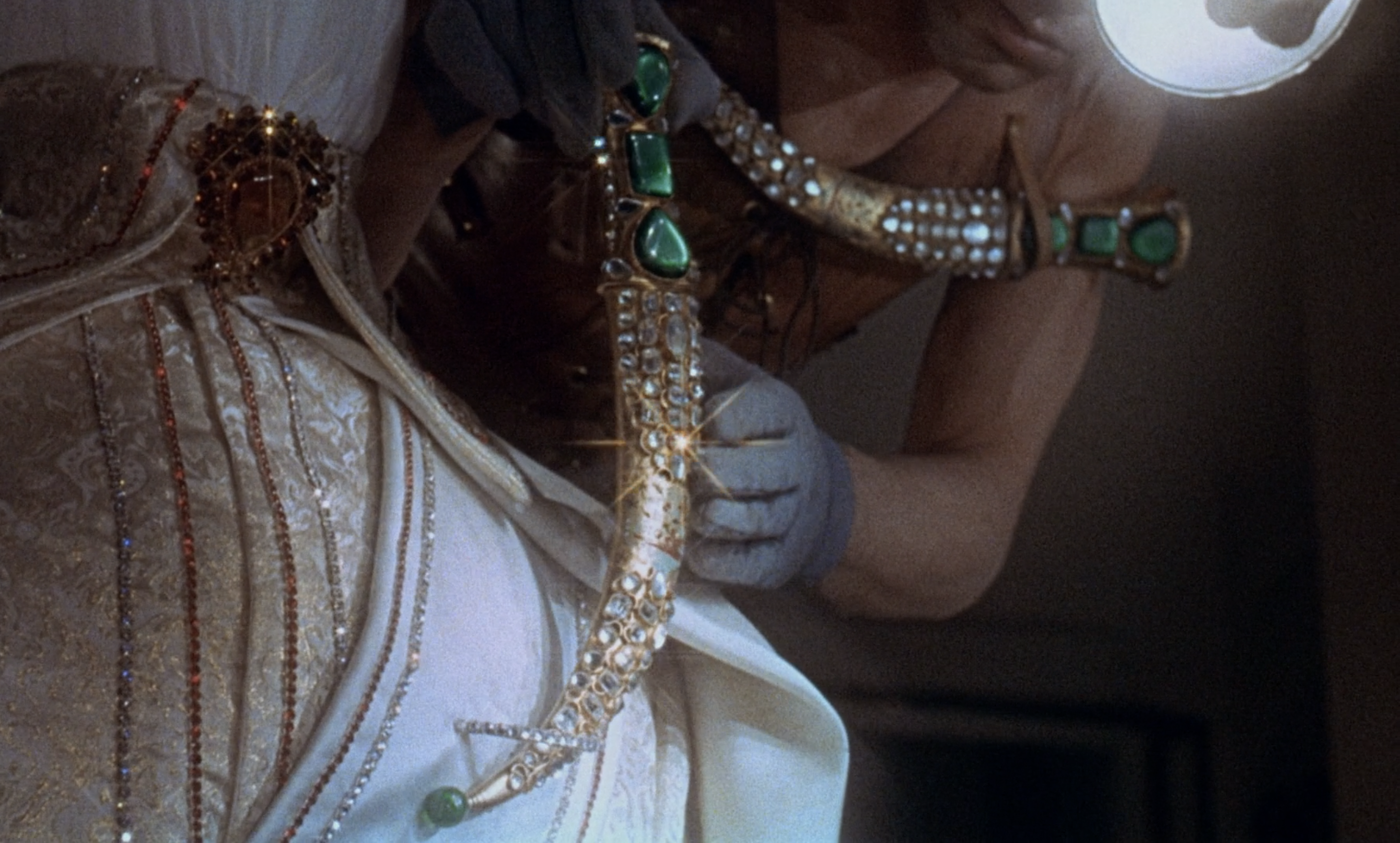

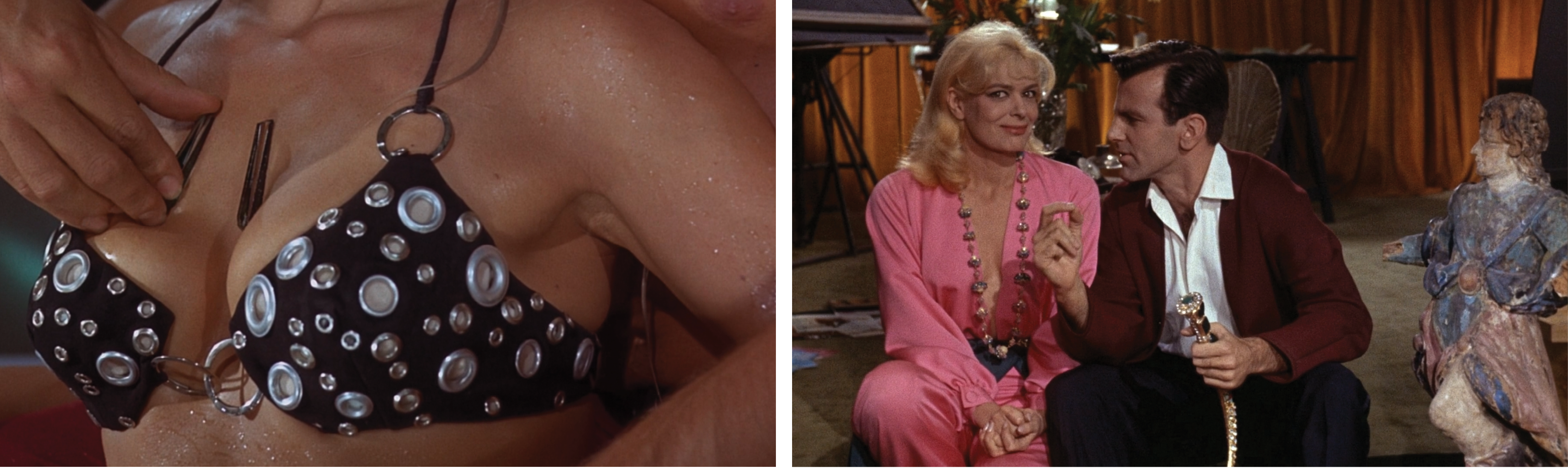

Left: Diabolik sets the emeralds on Eva Kant’s bare skin. Right: Walter Harper grips Elizabeth Lipp’s flawless replica of the Topkapi Dagger.

In Topkapi’s fanciful introductory vignette, Elizabeth Lipp—a self-identifying thief—cases Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace and directly addresses us over a saccharine orchestral score, illuminating her boundless desire to possess the Topkapi Dagger, a diamond-encrusted relic embellished by “the four greatest emeralds the world has ever known.” Bathed in red light and already wearing the second of fourteen mod getups she’ll don throughout the film, she places her fingers, gloved in white leather, on the glass vitrine and savors the sight of the sparkling dagger with wide, dewy eyes. She breathes heavily and then starts to choke up, remarking, in a thick Greek accent: “Forgive me. A strange thing happens to me … difficult to explain.”

Throughout both films, faced with the splendor of the surfaces presented to them, the viewer experiences a similar form of hypnosis. Here, the gritty neorealism that Dassin and Bava had favored during the forties and fifties gives way to Technicolor pizazz. Both filmmakers set out to stimulate desire in the viewer for the vibrant, shimmering emeralds. The bewildering forms of suspense they compose by illustrating the lengths to which thieves will go to obtain them are embellished by the artistry—of the filmmaker, and the criminals—exhibited in doing so. Neither Topkapi nor Diabolik strives towards verisimilitude or depicting the plight of the poor. Rather than inciting or reflecting political discourse, they revel in the display of their craft.

Both set up technologically secure spaces—an embellished Ottoman palace in Topkapi, a fictional fortified castle in Diabolik—to be permeated by technologically aided criminal collaborators via farcically complex procedures. They’re ridiculous films. But when they’re at their best, constructing enigmatic networks of angles, action, bodies, architecture, and tools, with their plausibility hanging by a thread (or suction cup), they transcend their mechanics.

The classical suspense deployed in Rififi is morally conventional in structure, in that it fosters audience allegiance with the sources of human morals: the love, for example, between parent and child or even symbiotic partners in crime. By deploying these relationships to dramatic effect, Rififi’s criminals maintain their humanity despite existing outside the social (or legal) moral order. Ultimately, they pay for their crimes with their own lives. In Danger: Diabolik and Topkapi, however, moral development and character psychology are largely avoided. In neglecting both subjective suspense—since the audience isn’t offered consistent identification with a particular character’s point of view—and objective suspense—in which the audience knows more information than characters in the story do—the focus shifts to the details of the protagonists’ physical struggles within complex technological systems. The audience becomes distracted from a larger moral framework and the consequences of the criminals’ actions. These flattened characters become components of extraordinary systems of action—and, as human actors, of representation—allowing kinetic suspense and material pleasures to flourish. This technique is neither moral or immoral; it is the amoral modus operandi of the aesthete. Its depths lie in the visual and aural surface of the work.

***

After Topkapi’s opening sequence, she recruits her ex—and now possibly current? (both films waste little time on the niceties of character development)—lover, Walter Hill, to plan a theft of the dagger. She finds him “up to his old tricks,” in the midst of a theft. As he stops to tie his shoe, he uses the car door handle as a pistol holster. This sets the stage for a world ripe with the visual and physical potential of objects.

The Mission is not as Impossible as it could be given that, during the heist, sweating onto Topkapi Palace’s weight-sensitive floor alarm doesn’t seem to be a concern, although, here, with a mockup of the floor, it is demonstrated that even a ping pong ball would set it off. It’s a slapstick rendition of musique concrète through a sight gag; each time the ball hits the floor, a blast of circus music plays. The mute acrobat Giulio, it follows, will have to break into Topkapi Palace without touching the floor.

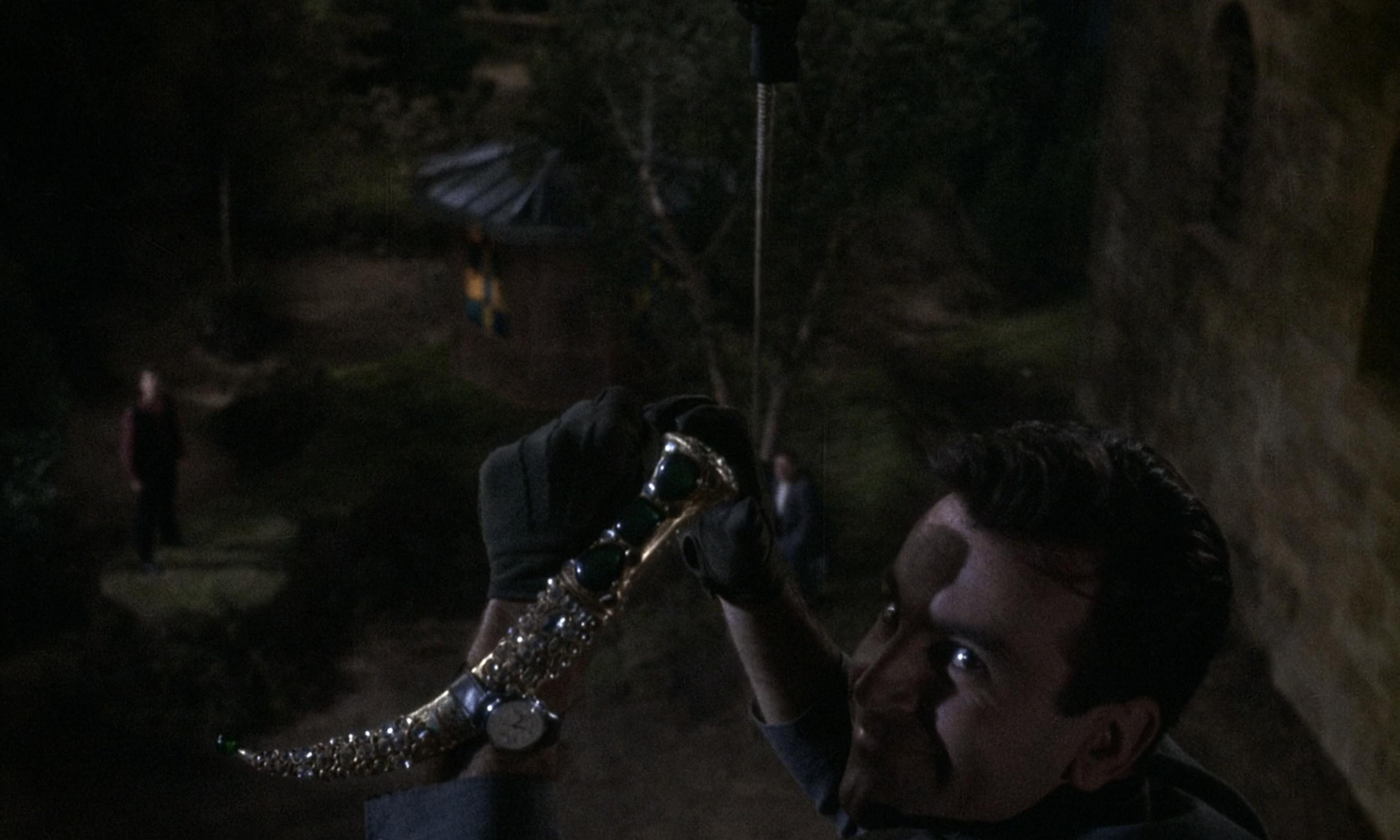

Unlike in Rififi, which features a laborious heist rehearsal scene that carefully instructs the audience as to its own mechanics, elements of Walter’s plan are cryptically unveiled across a tangle of comedic episodes that aestheticize the tools of the trade. At some point before embarking on the mission (time is also mostly abstract), said tools are displayed on a table like the scattered puzzle pieces of an unknown image that will fit together in the heist scene that follows. As will the accomplices themselves: small-time hustler Arthur’s greasy rope will be tugged by Walter’s elegantly gloved hands as it suspends Giulio by his snug leather utility vest. Later, when the objects’ technical functions are precisely detailed within the larger system, the attention granted to each part registers as excessively fetishistic.

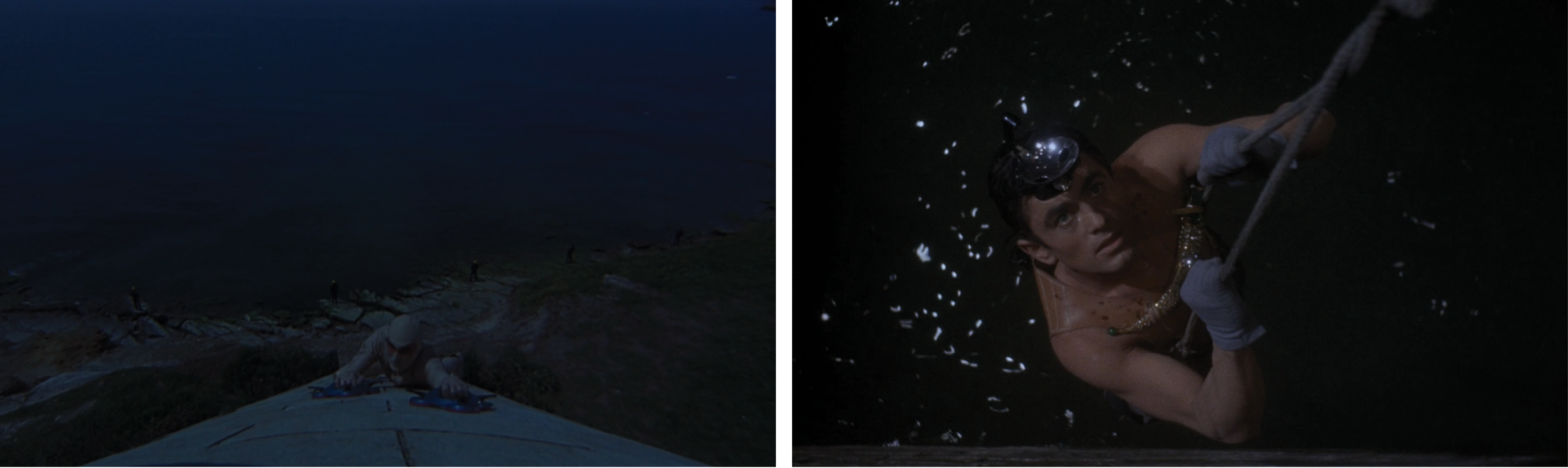

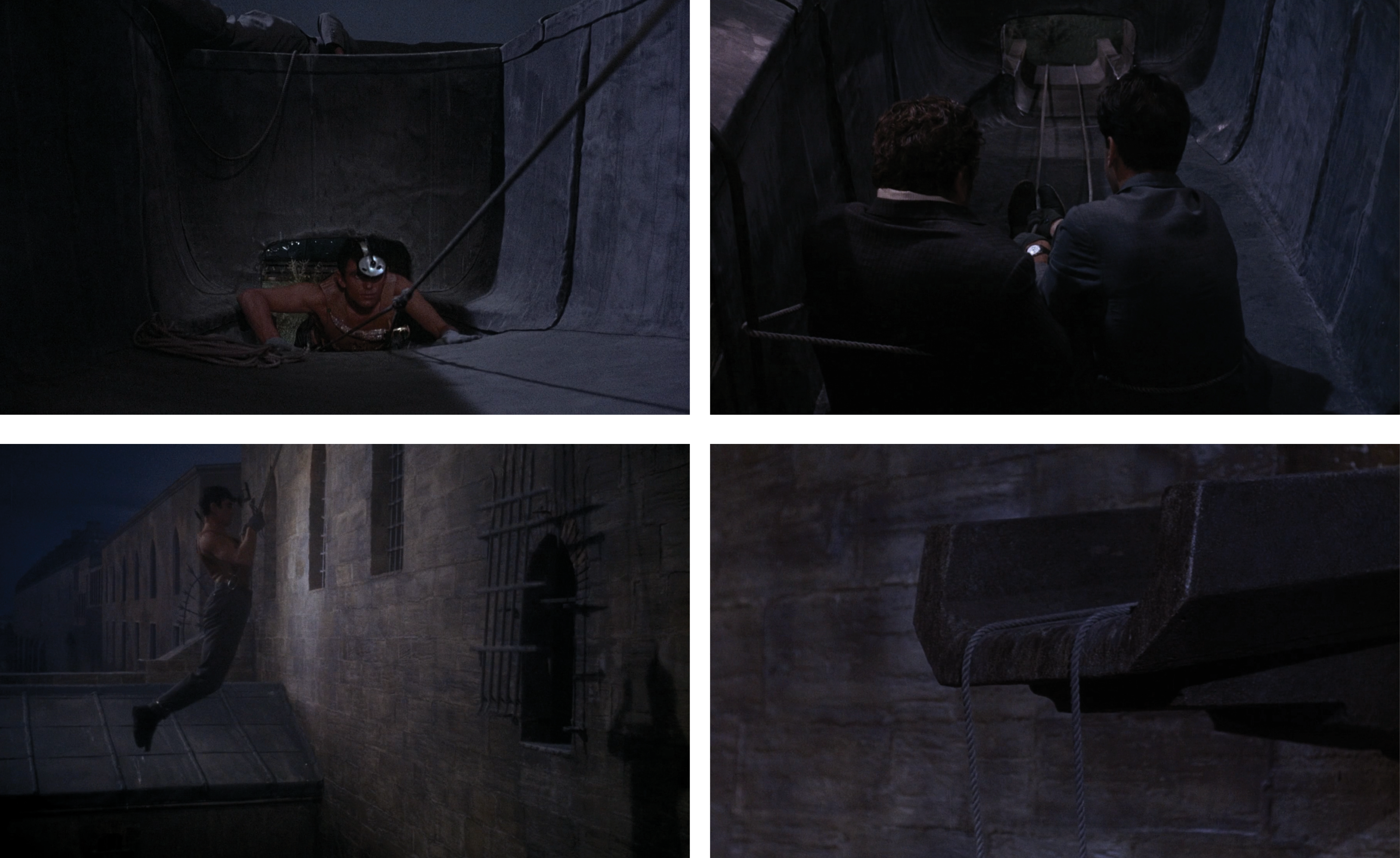

Giulio is lowered out of a drain on the roof of Topkapi Palace, with Arthur attached to the other end of one of the ropes. He cuts open the window grate and swings in, with the drain serving as a smooth guide for the ropes.

Topkapi, like Rififi, contains a half-hour heist sequence that uses silence for dramatic effect. While Rififi details a more plausible procedure in service of a moral framework, Topkapi offers a breathtaking display of “suspense” and “tension” manifesting literally on screen, as a system of ropes, mechanisms, and bodies lower Giulio into Topkapi palace. As with Elizabeth’s unmediated desire for emeralds, in which an emerald is just an emerald as opposed to an asset, suspense is often just suspense in Topkapi.

The intertwined objects of the heist are connected through amplifying insert shots, becoming actors in collusion with the thieves as they execute Walter’s boldly choreographed scheme, in which neither party ever sees more than half of the total system. Suspension of disbelief is achieved by the fragmentation of the viewer’s attention, as they attempt to track the algorithmic operation of an enigmatic plan that is both too textured to register as procedural and too complex to be grasped. Giulio glistens with sweat as he moistens tiny suction cups with his tongue, while the stained-glass window through which he enters casts a blurred reproduction of its colorful forms onto the palace’s interior. The scene is a masterful composition of surface, causality, covert mental modeling, and just having a feel for it—both within the fiction and externally, in the filmmaking.

Giulio (1) moistens a tiny suction cup and (2) uses it to prop open a stained-glass window, then (3) does the same for a suction-mounted device, which serves as an interior guide for the rope attached to the large glass display case that encloses the Topkapi Dagger. To indicate to Arthur that he’s ready to descend (4), he kicks the rope to send vibrations upward. Once lowered, he (5) uses the key that Walter fabricated to unlock the display case and then (6) attaches a suction clamp for it to be raised. Walter then (7) marks the rope to keep track of the position of the out-of-sight display case. With Giulio’s guidance, he (8) lifts the display case. Giulio then (9) replaces the authentic Topkapi dagger with the replica fabricated by Elizabeth, and (10) guides the display case back into position.

***

In a masterful transition, Diabolik uses a literal smokescreen to disorient police officers—disguised as high society individuals in a Rolls Royce—while transporting $10 million in cash from a bank.

In a film flush with countercultural posturing and anti-establishment sentiments (sex symbols dunking on cops, exploding tax offices, distorted guitar riffs) Danger: Diabolik (1968) is more commonly understood as a work of cinéma d’évasion—escapist cinema—that diverts viewers from social reality and moral questioning toward what is perhaps adequately suggested by the litany deployed in the film’s promotional campaigns: “police, sex, millions of dollars, supercars, diamonds, submarines, rivers of gold … drugs … white jaguar, black jaguar, Eva, Eva, Eva …”

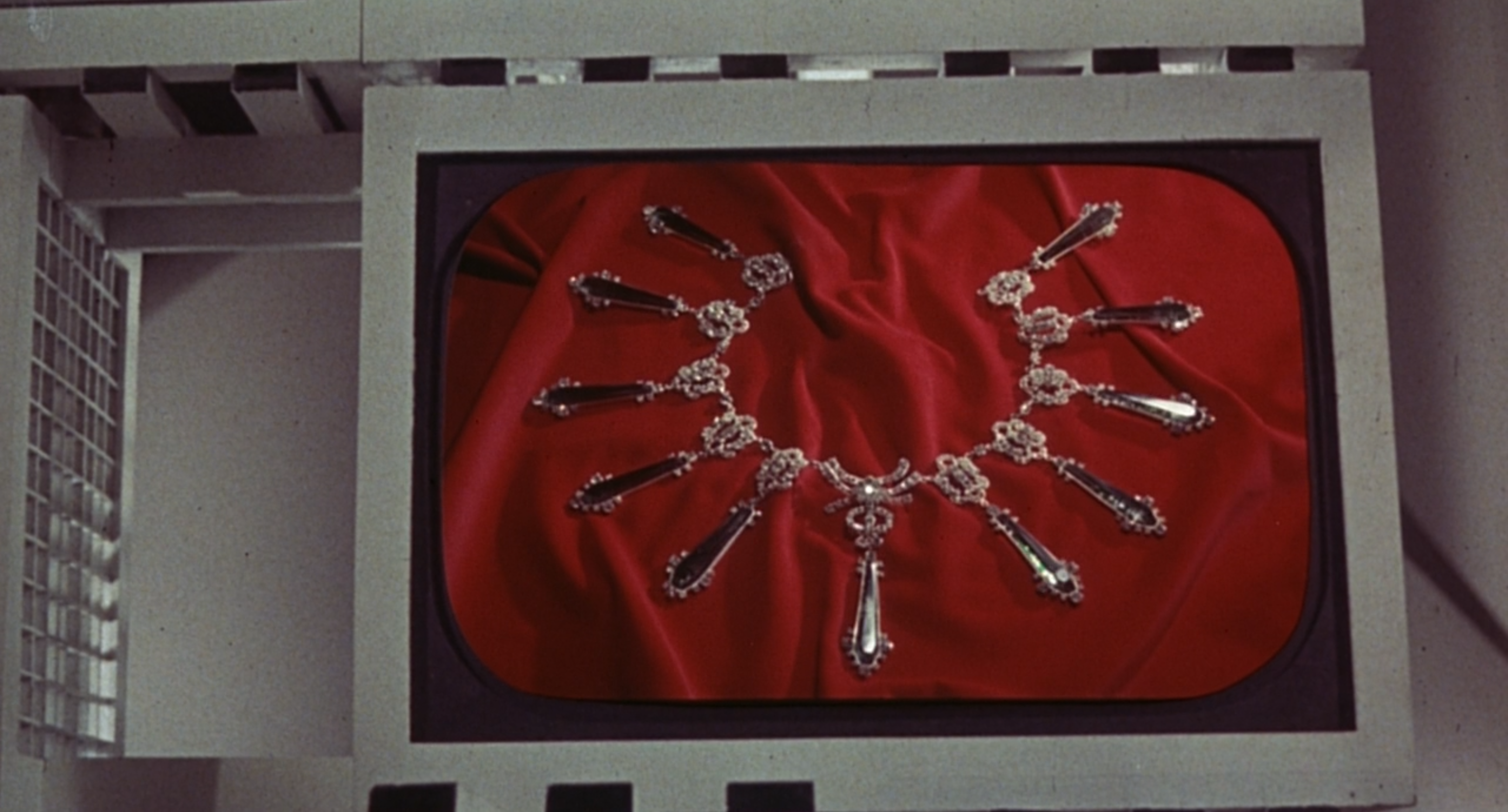

Following the introductory sequence, Diabolik and Eva Kant watch a news bulletin on the luminous entertainment tower that rises out of the middle of their rotating bed. Suddenly, the famous Aksand emerald necklace, resting on voluptuous red velvet, appears on screen. “Those emeralds …” Eva, mouth agog, whispers sensuously, her moist eyes drifting suggestively towards Diabolik.

While Diabolik and Eva, partners in coitus and crime, destabilize political and economic power by bombing their unidentified European country’s tax offices and pulling three heists ($10 million, a world-renowned emerald necklace, and a twenty-ton bar of gold), their ends indicate a perversely carnal materialism. Distinct from the circulatory drive of anarcho-capitalists, their pleasure lies in acquiring, owning, and displaying their booty—including each other’s bodies—through literal physical contact with material excess. A product of commercial filmmaking, Danger: Diabolik is also a deceptive lesson in object acquisition: a hallucinatory model for luxury, a fraudulent diagram for bedroom arrangement, an impossible fashion spread.

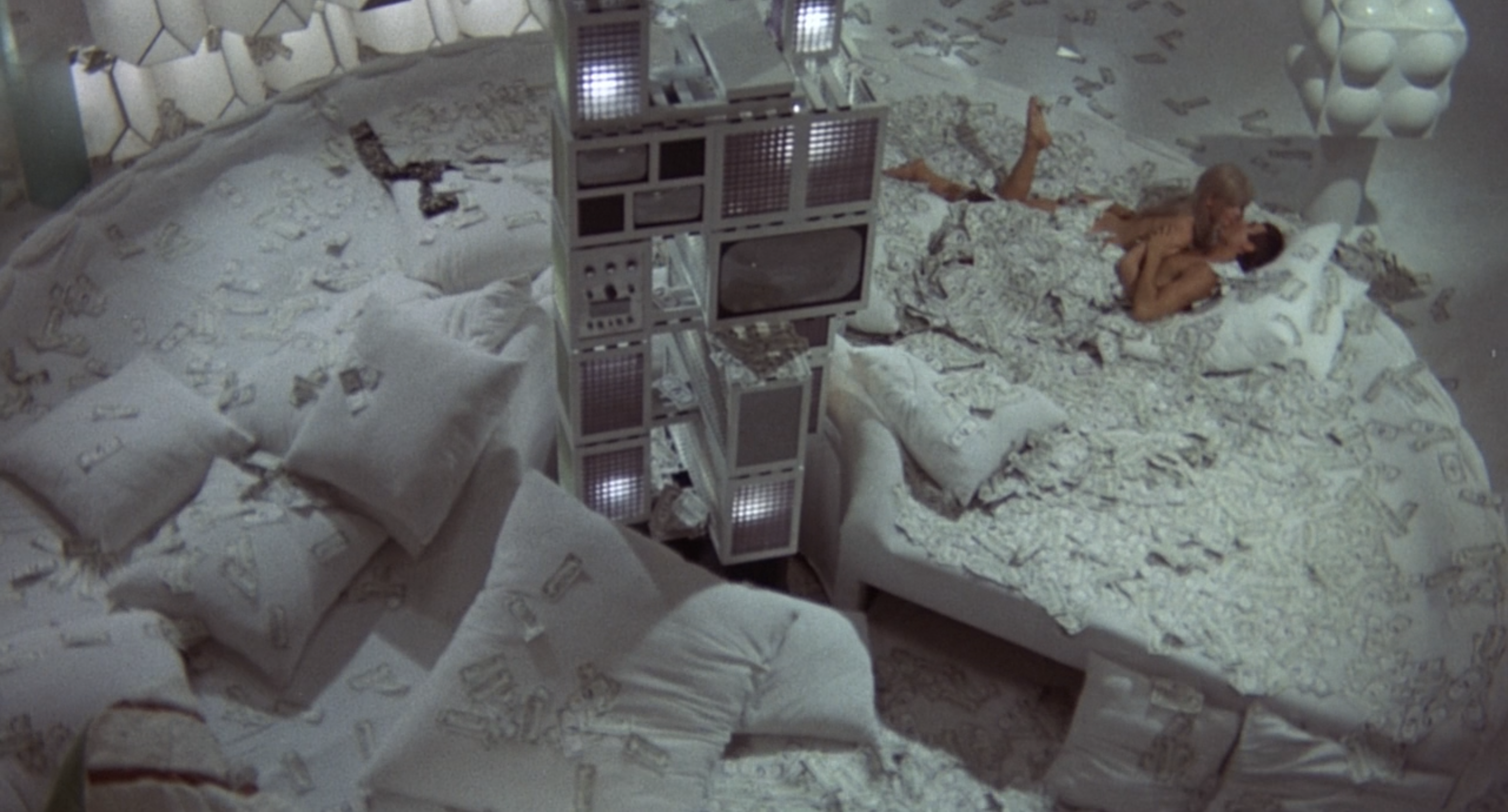

Following the opening heist, Eva and Diabolik make love in their rotating circular bed amidst $10 million in cash.

Like Topkapi, the film glosses over narrative drive and characterization in favor of audio-visual design, to the point that its loose episodic structure unfolds like three issues of the comic it was adapted from—Diabolik—stapled together. While, in the words of director Mario Bava, “all cinema is made for infantile brains,” this comic book movie still manages to wink knowingly (and often literally) at the audience as it presents visionary clusters of practical effects. If, in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), the spiral motif unites camera movements, architecture, costumes, and special effects, in Diabolik, a more abstract logic of the trick unites style and content. Trick photography, trick lighting, trick attire, a hidden lair, ghost-ridden vehicles, trapdoors, and so on, are all presented so quickly so as to constantly deceive and surprise the viewer.

Through matte painting, models, foreground miniatures, and forced perspective, a disorienting cinematic artifice is constructed. Their lair, for example, appears to be integrated into a grotto in a kind of virtual set design that is functionally analogous to more recent VFX technology. In both, the trick lies in masking the points at which the physical set gives way to the simulated depth, as in the illusionistic ceiling paintings of the Baroque era.

Screens, cameras, and mediatic representations of the object of desire abound. In fact, the trick-heist itself hinges on creating confusion between representation and reality. First, Lady Clark leaves her emerald necklace on the table, in full view of a security camera. Once she and Sir Harold Clark have retired to bed, Diabolik takes a photograph of the room from the perspective of the security camera, which is embedded in a portrait painting. He then uses a candle to mount the photograph in front of the surveillance camera. By the time security notices, Diabolik has made off with the emerald necklace.

At the conclusion of the film, in an ejaculatory spectacle of luxury, Diabolik melts the twenty-ton gold ingot he and Eva stole, spraying the liquid gold into smaller molds. But suddenly, the police infiltrate. Amidst a blaze of gunfire, Diabolik loses control, flooding the grotto with gold and encrusting his heat proof suit, leaving the police and Eva to believe that he is dead. Wealth for Eva and Diabolik remains tangible, a material adornment for their earthly bodies. This finale offers a kind of final moral position on Eva and Diabolik’s pathological form of materialism: unbound from value, their greed, as in the case of King Midas, leads to their corporeal undoing.

… Or, at least, it seems to. For this is soon revealed to be a trick ending: a beat before the credits roll, Diabolik winks and belts out his trademark laugh. There is seemingly no end to his exploits, and therefore no narrative—or moral—stakes.

***

Toward the beginning of Diabolik, in the first of many failed attempts by the powers-that-be to put an end to the lovers’ antics, the Minister of the Interior holds a press conference. He has reinstated the death penalty to dissuade criminals like Diabolik and Eva. But the couple disrupt the legitimacy of the conference by releasing “exhilarating gas” into the crowd, before taking “anti-exhilarating gas capsules” while the rest of the room erupts into laughter.

The structure of this trick unfolds with the kind of irony with which both Bava and Dassin approach their respective films. While they aim to elicit laughter from their audiences, the directors themselves are above the laughter. They make sure we’re aware that they’re aware of the films’ absurd pretenses and arbitrary worlds, deploying a protective self-mockery and puckish attitude towards the conventions of the heist genre.

Throughout Diabolik and Topkapi, characters compulsively reference the fact that they are performing roles: Diabolik winks at the camera and cycles through over ten costumes, Elizabeth Lipp addresses the audience and changes outfits thirteen times. While these distancing effects prevent emotional investment in the characters, they also make manifest the authorial presence and control of the director. Walter/Elizabeth and Eva/Diabolik are always a step ahead of not only their opponents but also the audience; like Bava and Dassin themselves, they know more about the work than anyone involved. In both films, the internal artfulness of the heist is intensified by the external artfulness of the filmmaking.

This artifice is linked to the pervasive presence of perversity, of those anarchic energies that are concealed beneath the often repressive veneer of human civilization and civility. The fictiveness of these story-worlds and the pandemonium they allow for—embodied and wholly motivated by the gem-crazy protagonists—give vitality to heists that rely on the vulnerabilities of institutional power and the unreliability of appearances: in Topkapi, the theft hinges on Elizabeth’s counterfeit dagger; in Diabolik, a misleading, set-dressed photograph is placed in front of the security camera.

If the post-neorealist Rififi seems to point through the veil of the screen to some other reality—blacklisted director’s biography, or the plight of the socially marginalized—Diabolik and Topkapi nestle into their representations. They affirm the play of appearances, albeit ironically, as their only reality. This strategy, rather than accepting the assumption of two levels—a representation and a reality independent of it—undermines our ability to make the distinction in the first place. Not, however, in order to lead us further astray from so-called reality itself, but rather to remind us that we are always involved with mediation.

Diabolik and Topkapi presented their directors with larger budgets than they had ever worked with. They made copious use of those funds, in constructed environments on studio sound stages, along with expressive lighting, extravagant wardrobes, and practical effects. The directors both self-consciously grappled with these systems of artifice beyond the frame by amplifying their effects within.

Each film seems to acknowledge that the production of narrative cinema entails ridiculous arrangements of collective behavior, through which casts and crews are subjected to an onslaught of gratuitous decisions—all in pursuit of a fantasy. At these stages in their careers, Bava and Dassin must have known the fantasy never turns out quite like one imagines: both films are imperfect gems. But, by then fully entrenched within their respective studio systems, they also probably assumed (correctly) that they would continue working. The thieves don’t end up paying for their crimes with their own lives; in fact, the protagonists are left at the outset of their next scheme. The films, therefore, don’t simulate the viewer’s social reality, they refer only to their own preposterous world-making: deceitful, obsessive, dopamine-induced, manic, technologically dependent, emotionally detached, perverse, shimmering, enchanted.

Andrew Norman Wilson is an artist based between Europe and North America. His work has screened at Sundance, New York, and Rotterdam, and sits in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, and the Centre Pompidou. Though principled, he leads a fraudulent life and his heists are many. He sees the return policies offered by Bezos and the Waltons as loan agreements; he lends them $1500, and the interest they pay is his use of a new editing hard drive. While TurboTaxing he hallucinates a DJ software skin, transforming the expense estimate sliders into Fraud Modulator functions. Occasionally he takes meetings with horny, neglectful dads to become a contract conspirator in the various wealth management schemes that constitute the art market. Otherwise he accepts unpaid exhibition offers from salaried curators and gallerists in far-flung cities and tacks on lecture stops at €150 a pop, spending as much time as possible as a guest in circulation, on sofas, so as to avoid paying rent anywhere. For ten years, he has been on Medicaid and food stamps. He is also an aspiring film director, and, following the production of a proof of concept short in 2021, his feature-length heist film Impersonator is currently in development.