Six Introductions That Will Change How You Read These Classics

In his excellent introduction to Edith Wharton’s The Writing of Fiction, the author and critic Brandon Taylor offers an observation that bears repeating: Literature from the past may contain dated worlds and ideas, but we can and should engage with it. Wharton’s works, for example, still present “some startling revelation about the way we live and write today,” he explains. Older writing can also give us “something to argue against.” Classic texts might remain static, but they are revolutionized over time by readers’ changing experiences and offer us the unique chance to be in “capacious communion” with them. Fresh introductions can help us achieve that intimacy.

Literary superstars such as Taylor have been eager to take on the role of both guide and medium, providing front matter that links the past with the present by placing classic texts in a contemporary context. Recently, readers have been treated to Merve Emre musing on Virginia Woolf in The Annotated Mrs. Dalloway, Esmé Weijun Wang expounding on Joanne Greenberg’s I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, and Margo Jefferson schooling us on Gwendolyn Brooks’s Maud Martha. Toni Morrison, Rachel Cusk, Rachel Kushner, Jennifer Egan, and Hilary Mantel have all written introductions.

The authors of the six forewords below ask us to reconsider our relationship with stories from the past. Through their interaction with the books they write about, they offer us new ways to read older works—and elevate this literary art form to new heights. Here, before we have made up our minds about a story, we can ask: What lasts? What should?

Karl Ove Knausgaard on James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (introduction translated by Martin Aitken)

In Joyce’s 1916 debut novel, the author’s now-infamous alter ego, Stephen Dedalus (seen later in Ulysses), makes his fiery debut. Young Dedalus rejects the religion he has grown up with, eschews the Irish traditions he has known, leaves home, and ultimately commits to becoming an artist by not serving that which does not serve him. In his foreword to the Penguin centennial edition of the book, the Norwegian sensation Knausgaard calls Portrait a “Bildungsroman, a coming-of-age story, perhaps the prime example of that genre in English literature.” Knausgaard predictably muses on identity, but he doesn’t dwell unnecessarily on it. Instead, his winding observations and philosophical musings steal the show. Detailed observations about Joyce’s seminal work—that it “swells” with “mood,” that it is really a book about the soul—allow a bigger picture to emerge. “Literature is never the preserve of others, and it knows no center, which is to say that its center is any place where literature exists,” he writes. “Only by refusing to serve, as Stephen does, may the artist do just that: serve.”

[Read: The book that never stops changing]

Lauren Groff on Yūko Tsushima’s Woman Running in the Mountains, translated by Geraldine Harcourt

Set in 1970s Japan, Tsushima’s novel—published in 1980 and reissued in 2022—follows the plight of Takiko Odaka, a young, single woman on the verge of having a child in a society that condemns unwed mothers. Tsushima captures the wild range of feelings and experiences that pregnancy and early motherhood inspire: beauty, suffering, boredom, banal domestic struggle, dogged determination to seek out happiness no matter what. The Matrix author Groff’s introduction does what few forewords do: It lets the author speak for herself. Groff quotes Tsushima, one of Japan’s most influential and prolific writers, extensively, intervening only to assist readers in sorting out the relationship between Tsushima’s life and work. As a result, instead of getting the rigid feeling of an expert dissecting their subject, one senses that Groff and Tsushima are kindred spirits: both are writers and mothers; both are interested in the complexity—and mundanity—of violence and ecstasy, joy and pain; both ask What is a heroine? What is heroic? (albeit from different places and times). They are letting us in on the secret that, perhaps, the answers are not what we have been led to believe.

Yiyun Li on Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace in Tolstoy Together: 85 Days of War and Peace With Yiyun Li

To understand and appreciate the genius of Tolstoy Together—which celebrates the experience of reading the novelist’s masterwork about the Napoleonic invasion of Russia in 1812 and its impact on several aristocratic families—try to imagine an introduction as a set of nested Matryoshka dolls. Tolstoy Together is like this. First is Li introducing War and Peace; then comes Brigid Hughes, the founding editor of the nonprofit publisher A Public Space, introducing Tolstoy Together; then the book returns to War and Peace, as other well-known writers and readers from around the world share their insights about the classic—and their personal and communal experiences reading it. Li’s introduction encompasses and unites all these parts; she writes that readers “want writers to articulate that for which we haven’t yet found our own words, we want our senses to be made uncommon.” She compares War and Peace to an old tree whose majesty needs no defending, ending with the unexpected but welcome admission that “fallibility is in everything I do.” Perhaps her ability to acknowledge her own imperfection emboldens her to break all of the rules? Here, a book becomes the preface to another book, and the introduction doesn’t belong to just one writer. With Tolstoy Together, Li gives readers the exact language she knows they are seeking.

[Read: The exquisite pain of reading in quarantine]

Sally Rooney on Natalia Ginzburg’s All Our Yesterdays, translated by Angus Davidson

In her introduction to Daunt Books’s handsome reissue of the late Italian author Ginzburg’s third novel about life before and during war, Rooney gushes about her “transformative” encounter with Ginzburg’s “perfect” 1952 novel, then bursts into a recap of the main events of the book and the author’s life. Ginzburg grew up in a family of antifascists and married a Jewish organizer who was later tortured and murdered by the Nazi regime he opposed. Her protagonist, Anna, also belongs to a family with dissidents doing their best to survive the Second World War. As a young wife and mother, she gives fugitives refuge in the cellar of her home. Rooney raves about plot elements and the “depth and truth” of the full cast of characters, exulting in Ginzburg’s—and Anna’s—recognition of the “supreme moral urgency” of the moment. It is our time, not just the 1940s setting, that Rooney tells us she is thinking of when she writes, “In times of crisis … there can be no ethics without politics.” Like Ippolito, Emanuele, and Danilo—Ginzburg’s young men who meet in secret to share books considered, by some, too powerful—Rooney says, as if to a friend, Here, you really must read this.

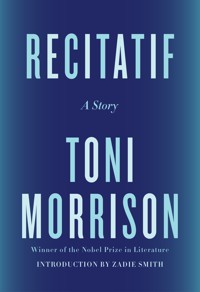

Zadie Smith on Toni Morrison’s Recitatif

Morrison, the Nobel Laureate and queen of American letters, wrote 11 novels—and only one stand-alone short story. Originally published in 1983 in an anthology edited by Amiri and Amina Baraka, Recitatif follows two characters—Twyla and Roberta—who have known each other since childhood. Readers are made to understand that one is Black and one is white, but not which is which. All racial identifiers have quite deliberately been omitted. One of the first things that readers may notice about Smith’s introduction is its size: It is as long as the story it introduces. Smith knows that Morrison has presented her readers with a puzzle and is eager to play along. She performs a close (very close) reading of the text that spans almost 40 pages, dissecting speech patterns, points of plot and character, and even the story’s title. But rather than attempting to solve the mystery (although, she confesses, she wishes she could), she unravels why the mystery matters and praises Morrison’s “poetic form and scientific method.” Morrison, Smith tells us, believed that a story could be an experiment. Smith seems to be asking why an introduction shouldn’t be one too.

[Read: Why Walt Whitman called America the “greatest poem”]

Colm Tóibín on Henry James’s The Art of the Novel: Critical Prefaces

When it comes to the prodigious and lasting work of the American-born novelist and critic James, one would be hard pressed to find a more apt or interesting guide than the Irish writer Tóibín. Tóibín wrote a novel, The Master, with James as its main character; he is also the author of All a Novelist Needs, critical essays on James and his works. In the 2011 University of Chicago Press reprint of The Art of the Novel—a curated selection of the prefaces James wrote for many of his own works—Tóibín leaves no stone unturned. Alongside the original 1934 introduction from the poet and critic R. P. Blackmur, he shares his own stunning reflections on James’s collection. James’s proclivity for dining out in 1877 London increased his interactions with “the most important figures of the day”; Tóibín’s delicious intro offers readers dramatic insights into the gossip (Robert Browning’s “talk doesn’t strike me as very good”) and real-life incidents (The Turn of the Screw was first told to James by the Archbishop of Canterbury!) that inspired his most popular works. If you are as good as James and Tóibín, even a foreword can be a masterpiece.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.