Rewinding to the Great Indian Empires Before the British Raj

To mention the British in India is to evoke memories of the Raj, of luxury and grandeur that went hand in hand with appropriation and exploitation, cricket and tea and pashminas that were products of the same set of conditions that brought famine and violence to multitudes, and left a sub-continent stripped, scarred and irrevocably divided.

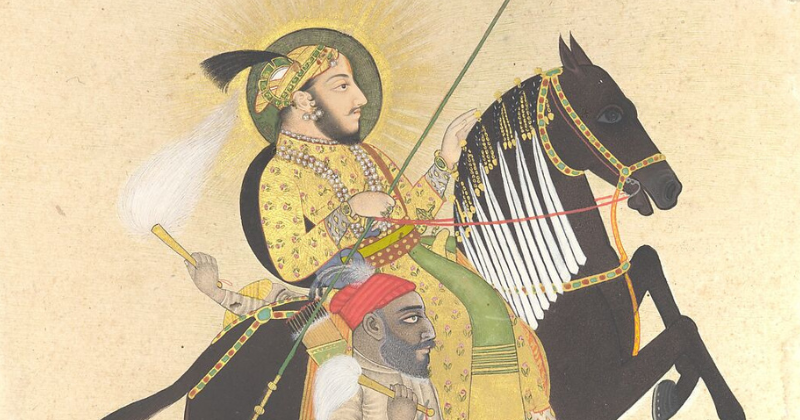

Yet there is a moment before that received history begins, when things were still in flux, and possibilities unrolled in multiple directions. The first decades of the seventeenth century represent just such a moment, when the Mughal empire in northern India was one of the wealthiest global powers, and England found itself a belated entrant into a world of trade and exchange in which others had already staked a claim.

My book, Courting India, is about the first English embassy to India, seen through the experiences of the man at its helm, Thomas Roe, charged with the responsibility of acquiring the elusive permits that would allow the English at last to set up permanent trading links with the sub-continent. This is not a moment that usually gets more than passing reference in histories of empire: the power-imbalance it sets up between India and England is too counter-intuitive, and Roe’s efforts too obviously lacking in results.

Yet that is precisely why, I argue, this moment demands our attention. It stands witness both to possible alternative roads down which the history of the two nations could have unfolded, and to the ways in which assumptions and expectations about other nations, other cultures, take shape and cohere, colored by our own memories and anxieties, fears and hopes.

In exploring the historical records of that moment, I wanted to pay attention not just to the unfolding of political and economic negotiations driven by those in power, but also to those who tend to get written out of the grand narratives of empire. Courting India is therefore not just about Roe, or even about the East India Company.

From the young Indian boy brought to England as part of a trading company’s attempts to demonstrate their civilizing mission, to the homesick English merchants terrified of dying far from home, from headstrong English women who insisted on entering unsuitable marriages, to equally headstrong Mughal women negotiating the world of the imperial politics, it is about multiple lives that were caught up in the process.

The list below has some of the books I returned to time and again, to understand the period, and the people, of both nations.

*

Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Europe’s India

Subrahmanyam’s book is a sprawling, thoroughly readable exploration of the evolution of European views of India in the roughly three centuries that lay between Vasco da Gama landing on the western coast of India, and the East India Company’s rise to power as the preeminent European presence in South Asia. This is a book that wears its prodigious range of learning lightly, moving from political history to literature, art to intellectual history with infinite ease. What it offers is a wonderfully sharp account of the intricate ways in which European ideas about India and what it meant to be ‘Indian’ went through layers of revision, even as the European commentators themselves changed as a result.

Richard M. Eaton, India in the Persianate Age, 1000-1765

Richard Eaton’s book is another history of extraordinary scholarship that still manages to remain accessible. It is a striking account of the linguistic and cultural complexity of pre-modern India, characterized by a degree of cultural and religious diversity which would shock and puzzle visitors from Protestant England, like Thomas Roe and his travel companions. It is also a useful reminder that the Mughals were not the only powers in the sub-continent. In the Deccan plateau, southern India, and Bengal, other powers flourished whose presence implicitly shaped Mughal worldview and actions—whether or not the newly-arrived Europeans fully grasped the implications of such internal interactions.

Jonathan Gil Harris, The First Firangis

Nations do not “encounter” each other in the abstract. That process takes place between individuals, each of whom carry their own assumptions and expectations. From physicians and artists, to pirates and priests, Jonathan Gil Harris’s collection introduces us to some of the very first travelers, from England, Europe, and beyond who arrived in pre-modern India, either willingly or unwillingly, and found themselves carving out new lives, and often, new identities.

As an expatriate living in India, Harris is particularly adept at illuminating sensory and bodily transformations, the ways in which sight and smell, the food we ingest and the sounds we hear become a part of us. His approach through micro-histories is very different from that of the more expansive books above, but no less illuminating, particularly when tackling the problem of recording lives of which the barest traces remain.

David Lindley, The Trials of Frances Howard: Fact and Fiction at the Court of King James

In 1615, the trial of Frances Howard and her husband, James I’s erstwhile favorite, Robert Carr, the Earl of Somerset, took England by storm. It had all the ingredients of a perfect scandal—sex, fraud, a whiff of same-sex intrigue, corruption, and murder. Howard was accused of poisoning her husband’s best friend, Sir Thomas Overbury. Roe had known Overbury in England, and while he was in India by the time the news broke, the Howard trials provide a superb and utterly gripping lens to understand the royal court and the country from which Roe had arrived at the Mughal court.

It is a portrait of a country in crisis, where misogyny, political paranoia, and intense competition for power held sway. If travelers carry their own worldviews with them, Roe’s was tinged with the same shades of anxiety and suspicion that we see in David Lindley’s account of the court of James I.

Ruby Lal, Empress: The Astonishing Reign of Nur Jahan

If Lindley’s book allows us a close look at the inner workings of James I’s court and contemporary English society, Ruby Lal does the same for Jahangir’s court, through another woman who has attracted as much criticism as Frances Howard, and significantly more fear, because of the power she was seen to wield. Lal’s biography of Nur Jahan, the favorite wife and consort of the Mughal emperor Jahangir, identifies itself as feminist historiography, that must often “look around” the towering male figures in received history. It excavates records either ignored or distorted by the biases of men who had written about Nur Jahan since her own lifetime and afterwards, and the result is a striking re-evaluation of both Nur and Jahangir, as well as the world they occupied.

William Dalrymple, The Anarchy

There are numerous books about the history of the East India Company, but Dalrymple brings a particular immediacy to the story of its fortunes in the century and half following Roe’s embassy. Historians have often returned to the way in which the East India Company’s ruthless rise coincided with their equally ruthless exploitation of civil strife in India following the collapse of the Mughal empire. Dalrymple draws attention particularly to the Company’s profiteering turned it into a mega-corporation of its time, wielding huge military as well as economic power.

Trade and war are mutually incompatible, Thomas Roe had warned the early East India Company during his embassy. Yet by the eighteenth century, the Company’s opinion about the use of military force had changed completely, and large-scale territorial conquests had laid increasingly larger swathes of India open to their pillaging. A new chapter in the history of both nations was about to begin.

__________________________________

Nandini Das is the author of Courting India: Seventeenth-Century England, Mughal India, and the Origins of Empire, available now from Pegasus Books.