On the Personalization of Craft; Or, We’re All Going to Die Soon Anyway

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the term craft, likely because I just finished a semester as a visiting professor at Columbia University. I have been using the word ever since I began the actual study of writing and literature but I confess that I have been using it with increasing confidence while my actual understanding of the word has been decreasing.

“Craft” has become an easy word to toss around without much thought, and the more you publish the more it seems you earn the right to wax eloquent about it. But as I sat and thought about it, the more I realized I do, in fact, have concrete ideas on craft, particularly the intimate personalization of that word and all that it does and can mean.

I grew up in New Delhi, and witnessed India change in the 90s as the economy opened up. It was a fascinating time to be living there, to see billboards changing overnight from advertising Thums-up, the local cola, to Coke and Pepsi. I saw air-conditioners coming into homes one room at a time, so for a few years, my brother and I would drag our mattresses into my parents’ bedroom to sleep at night. And I started to see, unfolding in front of me, the meaning of physical objects as markers of wealth, privilege, and identity.

My parents, both professors in Delhi at the time, invested in a full 32-volume collection of the Encyclopedia Britannica. It had to be pre-ordered and we had a carpenter named Sardar who was as excited about these books as my parents were, and he would come in the evenings with samples of wood and different designs and measurements to build this bookshelf shrine that would eventually house the encyclopedias.

Not just the encyclopedias though: the other hot object at the time was a fax machine, so we ended up with a bookshelf that had two levels at the top for the encyclopedias and then jutted out at the bottom for the fax machine; all of it was covered in Plexiglas to protect these objects of value from the Delhi heat and dust.

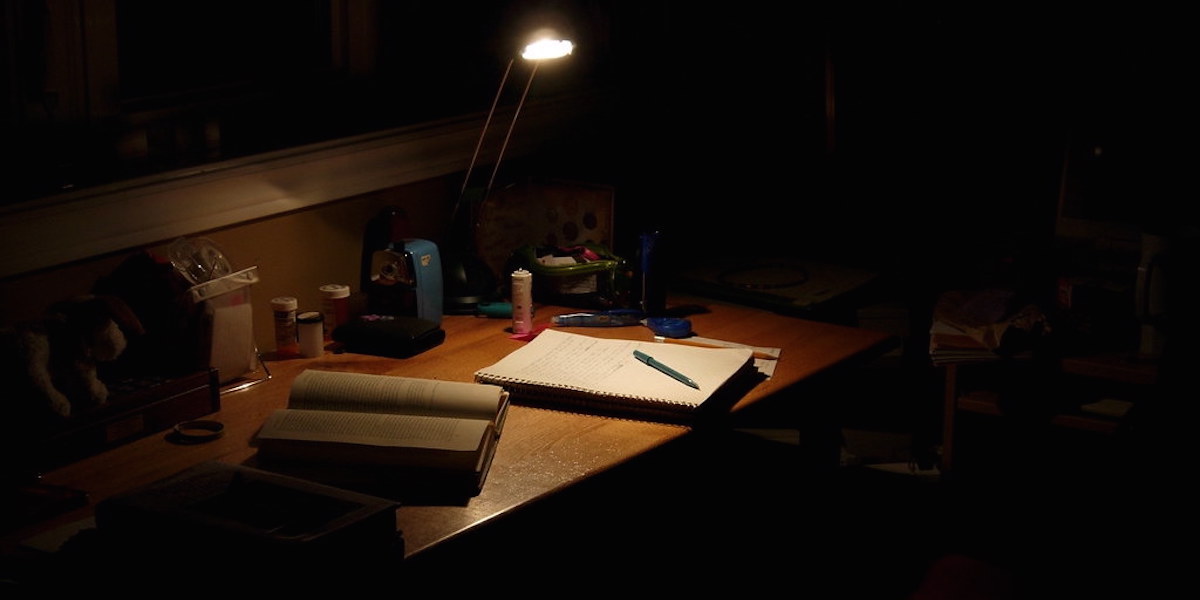

I fell in love with those books when they arrived. Every afternoon after school, I would remove one reverentially from the shelves and read its thin pages on any topic I could find. I remember the writing being so dull but the pages holding so much, as if under any given letter I might suddenly find a future somewhere in the world outside the suffocating Delhi summers.

I look back at that now and wonder: how does the idea of craft apply to what was written on those pages? Because it does apply, even to those rather dull paragraphs. There was no plot, no characters, no arcs, but to me, there was craft at work. Because craft is quite literally the technique of writing.

But we cannot talk about craft as prescription because to do so would be to erase the writer—craft, as a concept, is neither definite nor concrete. Instead we must think about craft in terms of the personal: craft as identity and ideology.

Literature is everywhere, not just in the hallowed pages of books. Literature is in the search for roommates on Craigslist, it is streaming into our bedrooms via Netflix, it is in Instagram captions, twitter, emails we send one another. Literature is on the walls of our cities in the form of graffiti.

It’s true what they say, art is never finished, only abandoned. Just like you have to commit to those first choices, you have to commit to the death, the completion, the abandonment.We can argue about whether or not any piece of writing is to our taste but that’s a different conversation. For literature in unexpected places, for found literature, it isn’t a question of knowing the rules to break the rules. The rules themselves are constantly changing. That’s what makes literature so exciting. Nothing is static.

It’s not that the rules are dated, it is that the rules don’t even apply in some contexts. My grandmother told my mother bedtime stories in Bombay and then my mother repeated versions of them to me in Delhi and now I tell my versions to my daughters in New York City. That’s literature—but it doesn’t follow any of the expectations or traditions we might consider “rules of craft.”

And if the rules are fluid, constantly changing, what is the point of the rules? And here is where I argue that the rules have to be personalized to each writer. Which is what we should be trying to do when we study craft, when we study creative writing. We are hoping to expand the breadth of what we read and what we write and what we are exposed to and deconstruct in order to find the rules and the techniques that become our individualized craft.

One thing I learned reading those pages of the Encyclopedias was the value of restrictions and control over language. The writers of those entries were all given very strict limitations—they had to choose each word carefully, stick to narrow columns as they summarized lifetimes of knowledge. They had to commit to each fact, each word, and by committing to those, also commit to all they could not use on the page.

Which brings me to one of my favorite David Foster Wallace quotes.

“In a Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” he writes:

I am now 33 years old, and it feels like much time has passed and is passing faster and faster every day. Day to day I have to make all sorts of choices about what is good and important and fun, and then I have to live with the forfeiture of all the other options those choices foreclose. And I’m starting to see how as time gains momentum my choices will narrow and their foreclosures multiply exponentially until I arrive at some point on some branch of all life’s sumptuous branching complexity at which I am finally locked in and stuck on one path and time speeds me through stages of stasis and atrophy and decay until I go down for the third time, all struggle for naught, drowned by time. It is dreadful. But since it’s my own choices that’ll lock me in, it seems unavoidable—if I want to be any kind of grownup, I have to make choices and regret foreclosures and try to live with them.

It is a bleak outlook on life, for sure, but this could just as well have ended with Foster Wallace saying, “If I want to be any kind of writer, I have to make choices and regret foreclosures.”

Because, like life, writing forces a series of choices that bring you to an ending. A death of sorts, perhaps, when you finish a piece of work. But let’s try to look at it a bit more optimistically.

In a first draft, decisions have to be made.

It sounds simple enough—characters have to have names, motivations, dreams and desires. Things need to happen that cause other things to happen but, troublingly, they also limit what can happen next. If character X is killed, she can no longer be alive. Such simple logic, such daunting prospects for fiction. I don’t want to stay for too long on the metaphor of the branches but fiction, perhaps unlike life, has more magic as you venture farther out onto each individual branch.

So, decisions. On the one hand, yes, you can always undo a decision in fiction. You can go back to page 37 and not let character X die. But then there’s fear. If you have already written 200 pages based on character X dying, to go back and change that will require unraveling everything. So instead you get stuck on page 37, trying to see the entire book in your head so you can make this decision and stick to it. But then the book will never get written.

An opening chapter, paragraph, or sentence of a book can only be written once the ending has been written. But an ending can be reached only once the opening is in place.

The very act of writing is the willingness to place ourselves in a closed loop with everchanging pieces and attempt to eventually push our way out.

Take a four-piece puzzle—you know the kind toddlers do as they learn to navigate shapes and the idea of continuity and form.

You put down the first piece and say to yourself, aha, an alligator’s head. So we’re going to make an alligator. The second piece is more of the alligator but a rather strange one perhaps, the third piece may still be the alligator but you notice it’s starting to look a little odd and when you reach for that final piece, it’s not an alligator at all, it’s the last compartment of a train.

So you go back to the first piece and you look around your house and you think the puzzle must have somehow got mixed up with another one and you finally find a different first piece that looks like a train. But by now, the straight four-piece structure doesn’t even fit anymore. The puzzle is a square. The puzzle is now three-dimensional and has sixty pieces. And you’re back at it, back rummaging through all the bins and drawers in the house looking for the butterfly pieces and probably going rather mad.

If the rules are fluid, constantly changing, what is the point of the rules?I want to talk about this specifically with regards to my novel, The Windfall. The Windfall is the story of a middle-class Indian family that comes into a fair amount of money and is moving from their original neighborhood to the other side of town, the posh side. When I first started writing the book, I couldn’t conceive of writing a novel. The idea of creating something so large and so complicated felt like a fool’s errand. I was going to try to write the subtle differences between the Indian middle class and upper middle? How to do that without having it sound like a thesis statement for an undergraduate anthropology class? For a long time I simply didn’t start.

Then I started to think about the world I had grown up in. I started to think about our neighbors and the dinner parties we had in this housing complex in which all the apartments looked the same and we ate rice and yellow daal with our hands and gossiped about whoever wasn’t there on that given evening. And that’s what I wrote. A short story, a dinner party, a roving close third-person perspective that could go in and out of most people’s POV in order to allow the reader to inhabit the space in between words said to one another.

I was not writing to say anything about the Big Topics. I was writing for my grandmother, who still lived on the first floor of one of the buildings of that housing complex. I made the decision to use Hindi in the same way I do when speaking in English in Delhi.

Thinking of my grandmother reading this was thrilling. She was an avid reader—reading in English, Hindi, Gujarati, and Marathi. She was funny, she was observant, and she was a little mean at timesI valued her opinion. That was another commitment I made—that of my first imagined audience. Like all my other choices, I had to narrow my imagined audience down to one in order to find the specificity of my voice.

It was no longer an anthropological essay with a thesis statement, it was almost an oral project in which I spoke to my grandmother. I assumed her knowledge of this world as my reader’s knowledge of this world and so I made the decision to explain minimally.

Like that alligator puzzle, everything kept changing, kept moving—for over five years I played around with these pieces. In the final version of the book, the one that is on shelves, I don’t think a single sentence exists from the “original.” But the commitments I made on those pages, the choices I made as I played, created the pieces where earlier there had been none.

We don’t get to do that in real life. On our deathbeds, we don’t get to go back and rewrite our births. We can perhaps abandon everything, all the choices we’ve made up until a certain moment, and escape into a solitary life in the hills but time has still marched on.

But, in the interest of optimism because really what is all this if not an exercise in optimism (a hope that tomorrow will exist and our words will matter) we can also say that fiction allows you to glimpse other branches, branches not taken, branches that you had to forfeit in real life. Now I’m moving away from craft and into therapy but life and art are, after all, adjacent if not deeply intertwined.

Like all my other choices, I had to narrow my imagined audience down to one in order to find the specificity of my voice.And it’s true what they say, art is never finished, only abandoned. Just like you have to commit to those first choices, you have to commit to the death, the completion, the abandonment. And that commitment can be the hardest.

The philosopher Robert Nozick, struggling to bring closure to an argument, wrote in the introduction of his 1974 book Anarchy, State, and Utopia:

One form of philosophical activity feels like pushing and shoving things to fit into some fixed perimeter of specified shape. All those things are lying out there, and they must be fit in. You push and shove the material into the rigid area getting it into the boundary on one side, and it bulges out on another. You run around and press in the protruding bulge, producing yet another in another place. So you push and shove and clip off corners from the things so they’ll fit and you press in until finally almost everything sits unstably more or less in there.

Quickly [he emphasizes the word and I want to emphasize his emphasis], you find an angle from which it looks like an exact fit and take a snapshot; at a fast shutter speed before something else bulges out too noticeably. Then, back to the darkroom to touch up the rents, rips, and tears in the fabric of the perimeter. All that remains is to publish the photograph as a representation of exactly how things are, and to note how nothing fits properly into any other shape.

I didn’t look at The Windfall after signing off on the proofs. Even when I got hard copies of the book, I couldn’t really bring myself to open it. I had quickly thrown myself into my next book and tried to look away as reviews started to come in and the book began to belong to the readers and the world. I was doing a reading at an event for the book and that was the first time I opened the actual physical book and I remember being in a taxi on my way to the bookshop one night and I was sitting with a pencil, finding new bulges, editing the actual finished product.

I will end with telling you about what a hassle those Encyclopedias became because not too long after they arrived, the Internet started to find its way into our lives.. All the knowledge in the world inside these tiny machines, no word limits, no space considerations.

Fortunately India is the land of recycling so we called the kabadiwalla, the man who goes from home to home collecting recycling and then paying you by the weight because he will resell it to factories to use as raw materials. Some ten, fifteen years ago, we pulled out boxes and boxes of these encyclopedias from a back cupboard and called the local kabadiwalla to come and collect them. They were still in decent condition and we assumed he’d appreciate the business but he came, took one look at them and got very irritated, saying, “Oh God, not another collection of those useless heavy encyclopedias.”

And he simply refused to take the fax machine.