Jerome Charyn on Finding Literary Inspiration at the Movie Theater

I wasn’t born at the Loew’s Paradise Theatre in the Bronx, but it did become my cradle. My parents were immigrants from Eastern Europe, and spoke a dialect that was unfathomable to me—a mixture of Polish, Russian, Yiddish, and Ukrainian. There were no kindergarten classes during World War II in my part of the Bronx, and so I had my first English lessons at the Paradise. It was Jimmy Cagney who taught me how to speak.

And I learned how to use a knife and fork from Greer Garson and Loretta Young, since I often ate with my hands at home or stabbed at the food on my plate. My mother went with me to the Paradise, the only movie palace on the planet that had a night sky right over your head, an orchestrated heaven, with clouds that sailed across a swollen field of stars.

We didn’t have any books in the house except for a pristine edition of Felix Salten’s Bambi, given to my mother at the first meeting of a naturalization night class she couldn’t afford to attend. But she wasn’t a total delinquent. She became my teacher in a teacherless time. We both discovered words on the page by tackling the language of forest animals who could talk much better than we did. We stumbled along, word by word. When Bambi’s mother died, we mourned for a month. This was in 1942—and it so happened that Walt Disney’s animated version of Bambi was released the same year.

Bambi wasn’t playing at the Paradise; we had to watch it at the RKO on Fordham Road.

What appealed to me most was where the narrative went and what it wandered into, how the puzzle of the story unpuzzled itself.What interested us was the barrage of epiphanies on the screen—the birth of the little prince, his learning to walk and prance in the forest, his shyness toward the little princess, Faline, his distrust of the open meadow, where hunters might arrive with their dogs and rifles and tents. “Man was in the forest,” Bambi’s mother says, as all the forest animals run from the dogs. Bambi’s mother is killed by the hunters, but we don’t see her death onscreen, and as we sat there at the RKO, we barely had time to mourn.

Disney was way ahead of his time in his depiction of Man’s desire to destroy the world around him, but the film, unlike the book, was also full of sentimental sop, with the refrain—“Love is a song that never ends”—repeated over and over again.

And yet I became a novelist that afternoon, at the age of five. I was able to catch the film’s narrative line, its melody, its poetic mood. I didn’t have to stumble with words on a page. Images on the screen became my vocabulary.

As my film education continued at the Paradise, I was never much concerned with directors. I liked certain actors, such as Gary Cooper, with his leanness and slow drawl. But what appealed to me most was where the narrative went and what it wandered into, how the puzzle of the story unpuzzled itself. Soon I became so adept that I could walk into the Paradise in the midst of almost any film and be able to reconstruct the story’s first half in my imagination. I was almost never wrong.

Then, in 1948, after I had just turned eleven, I was sabotaged by The Lady from Shanghai. Seasoned as I was, I still couldn’t follow the contours of the film and had to see it twice before I had the slightest idea what the hell was going on. Directed by Orson Welles, the film stars Orson himself as Irish seaman Michael O’Hara and Rita Hayworth as Elsa, a former high-priced courtesan now married to criminal lawyer Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane). At the time, Rita was actually married to Orson and in the midst of divorcing him. She was also the biggest box-office attraction in the world.

I couldn’t believe this was the same woman I had seen in Gilda (1946), where she plays a siren who does a striptease by removing only one glove, while she shakes her long red hair. Orson had her red mane shorn for the part of Elsa and turned her into a homicidal blonde. She seems mute in The Lady from Shanghai, a damaged femme fatale, who plans to murder Arthur and pin the blame on Michael, whether she loves him or not. The film ends in spectacular fashion, inside a hall of mirrors in an abandoned fun house. Elsa and Arthur shoot at one another as their images multiply in the mirror maze, and their personae disappear with every shot. First Arthur falls, then Elsa, and the shards of glass shattering around them seem to rip right into the screen like the thrusts of a dagger. It was as if the cinematic machine itself was dangerous and could harm me and other viewers as well as Elsa.

I have a funny feeling that the music of my language—my own whiplash of words—comes as much from images on the screen.After The Lady from Shanghai, I met with very few surprises. And then, in 1961, after I finished college and began frequenting art houses, I saw a film that utterly bewitched me and defied any definition of a narrative I ever had.

It was Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960), about a tribe of rich Italians who are utterly bored with their lives. Yet the heroine, Claudia (Lea Massari), has a hypnotic, half-mad intensity in her dark eyes, despite her malaise. I couldn’t stop thinking of Claudia as I watched the film, wondering what would happen to her.

Halfway through the film, Claudia vanishes and never appears again. I was enraged. And then I understood the boldness of the film. Our heroine disappears, and the story still goes on, almost as if she had never existed. For Antonioni, characters are only figures in a landscape, puppets at the edge of the frame, puppets that manage to breathe and move. It’s almost as if the cinematic machine, and not Antonioni, had decided to “kill” Claudia, and like The Lady from Shanghai, there were daggers hidden within the “mirrors” of the screen. That’s when I realized that the screen itself is “alive,” and as porous as human skin.

I published my first novel in 1964 and have been writing novels ever since. I’ve read most of the masters, but I have a funny feeling that the music of my language—my own whiplash of words—comes as much from images on the screen as from the narrative thrust and the melodies of Ulysses, To the Lighthouse, or Moby-Dick. I learned the art of storytelling at the movies. I remain bewitched by those images on the screen. They haunt my own novels, as if each of my books was its own mirror maze. I’m still right there with Bambi, with Elsa Bannister, and with Claudia’s hypnotic dark eyes, as I had always been there as a little boy at the Loew’s Paradise.

___________________________________

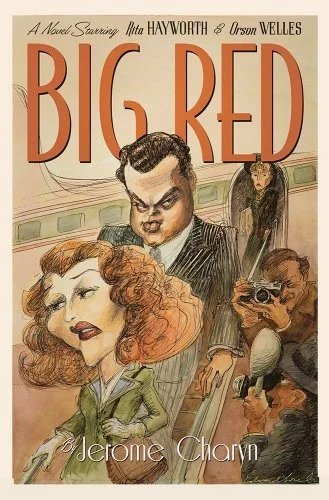

Big Red: A Novel Starring Rita Hayworth and Orson Welles by Jerome Charyn is available from Liveright Publishing, an imprint of W.W. Norton & Company.