In Nimblefoot, Robert Drewe returns to historical fiction after more than 25 years

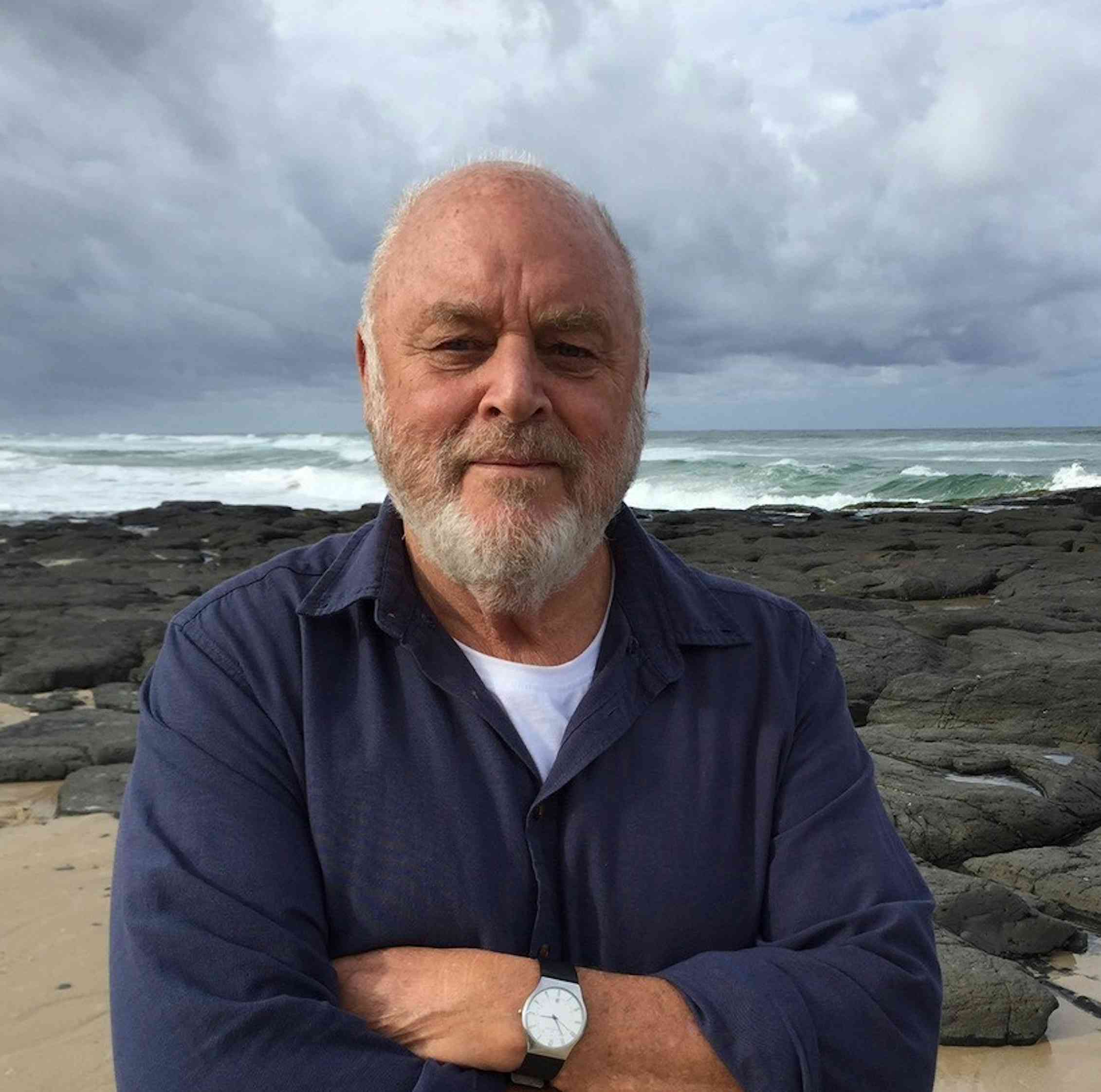

Nimblefoot is the eighth novel by Robert Drewe. His first, The Savage Crows, was published in 1976. He is the author of four collections of short stories, two memoirs, and numerous works in a variety of other forms.

He is also the recipient of numerous literary prizes, including the Commonwealth Writers Prize for The Bay of Contented Men (1989), and he has been shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Award twice – for his historical novels Our Sunshine (1991) and The Drowner (1996).

Review: Nimblefoot – Robert Drewe (Hamish Hamilton).

Nimblefoot is Drewe’s first work of historical fiction since The Drowner. In the intervening years, his interests have tended towards portraits of contemporary Australian life – some might even characterise these portraits as satirical. Whipbird (2017), for example – his previous novel – tells the story of a family reunion that takes place over one weekend at a family member’s vineyard. The book contains raucous debates between vegans and meat-eaters, the old and young, and even fans of rival football clubs.

Of course, Drewe established himself early as a social commentator on Australia’s middle class with the publication of his first short story collection, The Bodysurfers (1983), and he undoubtedly honed this skill in his decades-long career as a newspaper columnist.

A return to historical fiction

Drewe’s return to historical fiction in Nimblefoot has not been an easy transition. In the book’s acknowledgements section, he writes about “the difficult period of this novel’s writing – the most challenging of [his] career”. This struggle perhaps accounts for the four years that have elapsed between the publication of Whipbird and Nimblefoot. It is also possible to find traces of the struggle in the novel itself.

Nimblefoot tells the story of Australia’s first international sporting hero – a real-life person named Johnny Day, who competed around the world throughout the 1860s in a popular sport known as pedestrianism. Similar to the modern sport of racewalking, pedestrianism was a 19th-century form of competitive walking, sometimes over great distances, other times against the clock. Gambling was a big part of the sport’s allure for spectators, while substantial prize money attracted competitors.

Day won his first race at the age of eight, competing against adults. In his three-year career, he won more than A$8 million in today’s money.

Following the end of his pedestrianism career, Day went on to become a jockey. In 1870, at the age of 14, he won the Melbourne Cup riding a horse named Nimblefoot. Despite his remarkable achievements at such a young age, he then vanished from the historical record.

The first 66 pages of Drewe’s novel dramatise these seminal events in Day’s life. The novel gains momentum, however, when Drewe is released from the strictures of recorded history and begins to imagine why a teenage superstar like Day would simply disappear at the height of his fame. Without giving too much away, Drewe finds his answer to this puzzle in a murder witnessed by Day.

So begins Day’s life as a fugitive. He eventually leaves behind the state of Victoria and (unsurprisingly for fans of Drewe’s work) makes his way to Western Australia, where he moves between various locations and regularly changes employment to conceal his identity. Readers are thus afforded glimpses of a wide variety of historical settings, ranging from a seaside hotel and a quarantine hospital to a sheep and cattle property and a timber camp.

Balancing fact and fiction

While the murder and its repercussions are figments of Drewe’s imagination, he nonetheless attempts to balance fact and fiction. Day’s journey intersects with many historical figures and incidents.

Readers are treated to extensive descriptions of the first visit to the Australian colonies by a member of the British royal family – Prince Alfred, who visited in 1867–68, 1869, and again in 1870–71. Other notable historical figures who play an outsized role in this novel include the poet Adam Lindsay Gordon and the novelist Anthony Trollope.

Occasionally, it seems Drewe could not let his research go unused. For example, he writes:

He might also have mentioned that leeches had three mouths, both sexes, thirty-two brains and five million teeth and that Shakespeare wrote sonnets about them – but that might have been my fever.

Even the purely fictional elements are imbued with an excessive penchant for period research. Drewe quotes extensively from (fictional) newspaper articles, promotional posters, speeches, letters, a tub of ointment, and more. These excerpts are thoroughly convincing as historical documents, but more often than not they interrupt the narrative momentum.

Another consequence of this shaky balance between fact and fiction is that certain basic storytelling techniques have not been given due care and consideration. Foremost among these is the novel’s changing point of view. When Day is not present, the story is told using the third-person omniscient point of view. When Day is part of the action, sometimes the story is related in the first-person point of view, while at other times, for unaccountable reasons, it is told in third-person limited point of view.

It can be disconcerting when these point-of-view shifts occur mid-chapter and mid-scene, with only a section break for warning:

Johnny reminds himself who has the best form. Nimblefoot and he had won the Hotham Handicap only five days before.

He takes a big breath.

*

I give him his head. I’m balanced over his withers so that I won’t throw off his forward surge.

There is no doubt that these shifts in point of view are intentional, but their purpose is unclear. As an experimental technique, it does not resonate with the novel’s themes. In almost all other respects, Nimblefoot is a traditional bildungsroman.

The hallmark of a bildungsroman is that it follows the growth and development of its young protagonist. It is therefore essential that this character is engaging. Day does not disappoint in this regard. His slow maturation endears him to the reader, and his journey to adulthood is full of surprises.

Furthermore, Drewe’s descriptive prose is as gorgeous as ever:

As he walked the cliffs, the same pedestrian route every day, to the lighthouse and back, he noticed how summer bushfires had burned everything, even the least flammable vegetation – the pigface and saltbush – down to cliff edge and high-tide mark. The fires had pared trees into gesturing sculptures, melted seashells and limestone pebbles and cuttlebones.

There is little doubt that Nimblefoot deserves to – and, moreover, will – be met by an appreciative audience. Many readers will welcome Drewe’s return to historical fiction after more than a quarter of a century.

But those who enjoy Drewe’s contemporary fiction, including its satirical contributions to social commentary, might be left wondering why he has chosen to fictionalise this particular chapter from Australian history. More to the point, they may wonder about the contemporary relevance of Johnny Day’s story.

Our Sunshine reimagines the life of the infamous bushranger Ned Kelly, and The Drowner is about the celebrated engineer C.Y. O'Connor’s quest to build a 500-kilometre water pipeline to the inland city of Kalgoorlie, but Nimblefoot features a relatively unknown historical figure. Shining a light on Johnny Day’s story does not have the same potential to, for example, reveal new truths about Australian identity and myths of nationalistic progress. Perhaps as a result, Nimblefoot, though entertaining, does not linger in the imagination.

Read more: Witchcraft and fascism collide in Jane Rawson's imaginative new novel

Per Henningsgaard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.