How a Single Cookbook Shaped What It Meant to Be an “American Woman”

When my grandmother was a young girl and expressed interest in learning to bake cakes, she was gifted a copy of Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book. In 1950s America, Betty Crocker was the epitome of cake, and her cookbook was its most expert guide. With its 449 pages of recipes and photograph after photograph of bright pink chiffon cake and fluffy angel food cake, the book was impressive.

“I was starstruck,” my grandmother told me. “And I was proud that I owned it. It was my own cookbook.”

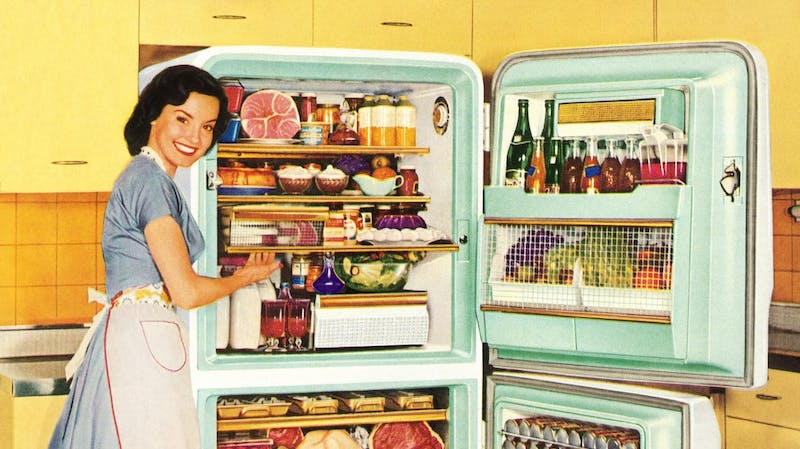

As she flipped through the book’s pages, she noticed something about the dozens of illustrations of pearl-bedecked, apron-clad women taking cakes out of the oven: “They didn’t look at all like my mother,” my grandmother, née Elena Maria Fiorello, told me. Her mother, Eleanor, was a Sicilian immigrant with a tomboy-meets-Audrey Hepburn style; she wore peg pants with ballet flats or jeans with loafers.

“I don’t think my mother owned an apron,” my grandmother said. “And she wouldn’t be caught dead in a house dress.”

Eleanor Fiorello, my great-grandmother, was an anomaly for her time in more ways than one. Much like her daughter would later do, she balanced raising children and keeping a home with a strong presence in public life. Eleanor had been forced to drop out of high school to work in a shirt factory but went on to become a respected leader in local politics, serving as a selectman and then as deputy sheriff (she was also a champion sharpshooter). As an immigrant, a woman, and an outspoken Democrat, Eleanor Fiorello was an unlikely combination in 1950s Connecticut. She still put food on the table every night—and spent hours simmering homemade red sauce on Sundays—but she hardly fit the Betty Crocker mold. And neither would her daughter.

Not only did it guide generations of women in the kitchen; it was a cultural force, functioning as a blueprint for what it meant to be a good wife and mother.Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book is the best-selling cookbook in American history, with approximately 75 million copies sold since 1950. Not only did it guide generations of women in the kitchen; it was a cultural force, functioning as a blueprint for what it meant to be a good wife and mother. Cookbooks are one of those banal texts that we might ignore or dismiss, but this one, like so many others‚ tells a story about U.S food and everything that is wrapped up in it: family, power, class, culture, ethnicity, gender—and what it means to be American.

When eight-year-old Eleanor arrived to the US from Sicily in 1920, anti-Italian sentiment still gripped the nation.

“There was a lot of pressure for them to assimilate,” my grandmother said of her family. “My grandfather demanded that more than anything—if his wife slipped back into being too not American, or not American enough, he would remind her that that was important.”

Her grandmother’s English was poor and heavily accented, and despite her dresses and high heels—“she looked like Betty Crocker,” my grandmother remarked—some people still stared at her as if she were “less than a human.” The family took pains to assimilate, and by the time my grandmother was growing up the message was clear: We are Americans.

Around the same time my Sicilian family arrived on the East Coast, Betty Crocker was “born” in Minneapolis to the Washburn Crosby company (what would soon merge with other milling companies to become General Mills). Betty’s birth had been something of an accident. In an advertisement for their signature product, Gold Medal Flour, Washburn-Crosby included a puzzle that readers could solve and send in for a prize. Much to the surprise of the all-male advertising team, thousands of women included letters alongside their completed puzzles, asking why their dough was lumpy or how to make their cakes rise.

The male employees were loath to sign their names to any letters in response, and so they invented a new name—Crocker for William G. Crocker, a recently retired executive, and Betty because they thought it sounded wholesome. After an informal contest among the women of the office to sign the letters, a secretary’s signature was chosen. With that, a handful of businessmen selling flour invented a fictional homemaker—and the perfect woman for the first half of the 20th century was born.

With the rise of radio in the early 1920s, Betty Crocker quickly became a star, with actresses and staff of General Mills bringing her to life on the airwaves. The arrival of World War II skyrocketed Betty to a new level of fame. General Mills distributed millions of pamphlets on the war effort, while Betty broadcast a message of community and patriotism on her widely popular radio show. In 1945, Betty Crocker was named the second-most influential woman in America by Fortune magazine—just behind Eleanor Roosevelt. At her height, she received as many as 5,000 letters per day.

Many of the women who wrote to Betty Crocker believed she was a real person. They often addressed their letters as “dear friend.” And they wrote not just of their cooking but of their marital problems, their children, sometimes their feelings of inadequacy or a lack of purpose.

A handful of businessmen selling flour invented a fictional homemaker—and the perfect woman for the first half of the 20th century was born.For millions of women, Betty Crocker was not just a name on a cake mix: she was the guide to whom they turned for support about everything in their lives, both in and outside of the kitchen. As such, her cookbook had an unprecedented impact on women’s lives: for many, the messages that they received about how to be a wife and mother came from the trusted friend they had known for years.

By the time Crocker’s comprehensive cookbook was published in 1950, she had been a national sensation for nearly three decades. In the first weeks after the cookbook was published, it was selling a staggering 18,000 copies per week. This cookbook is 1950s domesticity incarnate: encouraging women to strive for perfection in their kitchens and to see homemaking as an “art.” But for immigrants and the children of immigrants, Betty also seemed to teach another kind of lesson.

Looking back, my grandmother explained: “Of course I was American because I was born here, but I can see that it Americanized people. I look at what a strong influence that cookbook had because it taught you how to be an American woman.”

*

A little more than ten years after receiving the cookbook, my grandmother got married at age 18, and Betty Crocker continued to accompany her in the kitchen. Meeting her husband’s Irish-American family proved to be a clash of cultures, especially around meals.

“There were certain assumptions, that my food had to be strange,” she said. “I was trying to make their food, which to me was tasteless,” she added. Her family, for their part, jokingly referred to my grandfather (David McHugh), as “Davie Mercuto,” and quickly introduced him to their homemade wine that my grandmother described only as “strong.”

My grandmother never became a Betty Crocker devotee, though the cookbook did bridge the cultural divide. After an effort to impress my grandfather with her family’s red sauce failed—he said it was good but didn’t taste like Chef Boyardee—my grandmother turned to the cookbook.

“Here I was chasing my tail trying to do something good, so I did refer to the Betty Crocker cookbook.” She made roasts—and even Irish soda bread.

But the constraints of the suburban lifestyle espoused by Betty Crocker—the mandate to have a home-cooked meal every night and new hors d’oeuvres for the dinner parties—chafed my grandmother. After her husband graduated law school, my grandmother found herself thrown into the competitive world of young lawyers. The word she used to describe this period of their lives was “plaid.” The men wore plaid pants, and the women wore long plaid skirts. In an effort to fit in, she donned the requisite plaid skirt and turtleneck sweaters at every law firm party.

“It made me feel like I was choking, because I was like my mother, and I was uninhibited like her,” she said. She soon started to wear what she wanted, to do what she wanted to do: my grandparents sometimes took their young sons out for day trips on their twin motorcycles.

After her children were grown, my grandmother started searching for more. She attended classes at her local community college, and it was there that a friend passed along an advertisement in the New York Times: Yale was accepting adult students. After a year of wavering, she applied on a whim: “I needed to prove that I could do it,” she told me.

She could do it, it turned out. Alongside a rarefied swath of 18-year-olds from across the country, my fortysomething grandmother was accepted to Yale. On her first day of college, walking through the iron gate, she had one thought: “My mother would be so proud right now.”

When it came time to pick a major, she chose American Studies. She finished Yale and then graduate school at NYU, and at times when my grandmother was working long hours, my grandfather picked up the slack in the kitchen. He learned some of her Italian recipes, and I remember him calling her when she was working late to ask what she wanted on the menu that night. When my grandfather fell ill last year, the thing he complained about most to me was the hospital food. When I asked him what I could bring him to eat, he didn’t hesitate: “Grammy’s meatballs.”

My grandmother occasionally consults Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book for roasting times, or a cake here and there. Her well-worn copy is yellowed with age. Now the cookbook is mostly a memory, a cultural object my grandmother studies with an almost anthropological eye. For her, Betty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book has been dwarfed by years of reading and learning, one book among a crowded shelf of many others.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Americanon by Jess McHugh. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Dutton Books. Copyright © 2021 by Jess McHugh.