How a Secret Becomes a Story: Melissa Fu on the Importance of Listening to Elders

It is Christmas, 1998. I’m home in New Mexico for the holidays, on break from graduate school in New York City. Later this afternoon, my father will get out his beloved Betamax and watch his copy of Casablanca for what must be the hundredth time. But right now, he is doing something unheard of: telling me and my eldest brother about his youth in China and Taiwan.

In my entire twenty-six years, he has never told us anything about his past. It is a taboo topic in our house. Initially, we avoided it, afraid of angering him. Eventually we ignored it, figuring it didn’t apply to us.

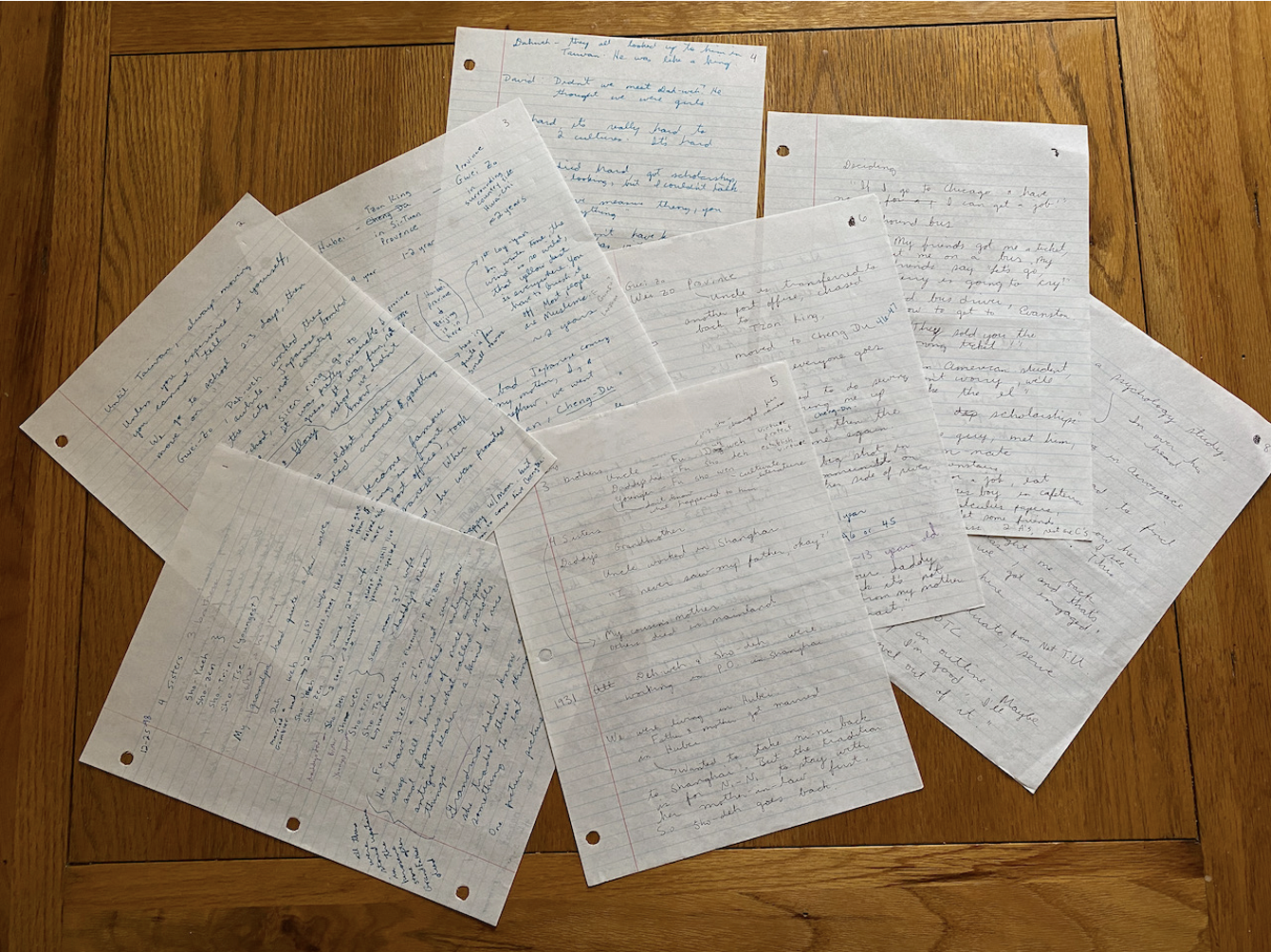

My pen scrambles to catch his words. I make my best guesses at the spellings of cities, towns, and relatives I’ve never heard of. I don’t dare interrupt, don’t dare break the spell. I don’t want his silence to return. When he finally stops, I have covered eight pages of loose-leaf paper, front and back, with a hurried scrawl of names, dates, and details: a wooden monkey puzzle picture, kerosene bottles, a valuable hand scroll, watermelon seeds.

In the years that follow, I hold on to those notes, always knowing where they are, certain they are important but unsure what to do with them. In truth, part of me is frightened of them. Occasionally I take them out and reread them, checking to see if they are still real. I wonder if they, like so much of my dad’s life, should continue to be a secret. Are these stories only meant for me and my brothers’ ears?

Notes I took in Dec 1998 about my father’s early life in China and Taiwan.

Notes I took in Dec 1998 about my father’s early life in China and Taiwan.

How does a secret evolve into a story? And when do you tell a story? Is it when you think it’s safe enough? When there is no longer any need to protect someone or something? Can the passage of years make the telling a celebration instead of a betrayal?

From the beginning of the project, there was an urgency, a sense that I had to write this story now. A sense that time was running out.Now when I think about the day my father told his stories, I realize that he was entering a peaceful period of his life. He had recently retired, and my parents had moved to the city of Albuquerque. My brothers and I were all busy building careers, families, and lives of own. He was enjoying being a new grandfather. Maybe, for the first time in a long time, instead of looking at the past with sorrow and the future with caution, he could consider his life with reflection and hope. It was a time he could tell the stories he had carried safely and silently for so long.

Some years later, a handful of peach pits he tossed into the backyard took root and started to grow. To our family, this was nothing short of a miracle. After years of trying and failing to grow fruit trees at our old house, here in his new home, he had an orchard, albeit an accidental one. As a tribute to him and his trees, I wrote a short story about them. It was a passable story, but it didn’t do justice to who my father was and why it mattered that his peach trees grew.

One of my father’s peach trees in bloom a few months after he passed away.

One of my father’s peach trees in bloom a few months after he passed away.

By then, nearly two decades had passed since the day he told us his stories. I had become a teacher, married, had children and moved to the United Kingdom. After various jobs in education, I was starting to wonder what would happen if I took my writing more seriously. Determined to improve my peach tree story, I took out those old notes from my father and studied them again.

The notes amounted to a list of places and dates peppered with small anecdotes and side comments. We are a very healthy and handsome family. You have good health, you got it from me! and It’s hard, it’s really hard to live in two cultures. My favorite: No matter what, your daddy pretty bright. I think it’s not from my father, but from my mother. Nainai was very smart. And this heart-breaking understatement: Chinese history is sad.

As I reread the pages, it dawned on me that to do justice to the miracle of my father’s trees, I had to better understand who he was and the extraordinary times he lived through. The more I thought about it, the more certain I became: The narrative connecting these notes to my father’s peach trees was the story I really needed to write.

It took some detective work to translate the notes to an actual journey. My dad had quite a strong Southern Chinese accent and I had written down the various locations phonetically. I remember poring over a map of modern China, saying the names of each city aloud, trying to match the sounds I was making with places that could correspond.

When I had traced their possible journey, it seemed unbelievable: nearly 6500 km! It couldn’t be right, they couldn’t have gone all that distance, much of it on foot or steamboat. But there were details that confirmed I was on the right track. He remembered times in the cities of Chongqing and Chengdu. He mentioned living in small towns near Beijing in the Hebei province. He recalled a period in the Henan province when they travelled along the Yellow River. The Yellow River always makes trouble, he said. Of the city of Luoyang, he recalled that In the winter, the wind is so wild that yellow dust is everywhere. You have to brush it off. Most people are Muslim.

I needed to know more, much more, to write a coherent story. I began to research the Sino-Japanese and Chinese civil wars. With a better grasp of modern China’s complex history, I returned to my map. Now I could see how the family was moving with the Nationalists, led by Chiang Kai-shek. They zig-zagged across China, chased first by the Japanese, and later, by the Communists. As I imagined my family’s journeys and choices, the pages of notes transformed. With streamlining here, expanding there, additions and subtractions, I was turning a timeline into a story.

From time to time, I considered asking my father to revisit his memories, but I just couldn’t. I didn’t have the heart to ask him to think about those sad times again. Besides, there was a freedom that came with not knowing the truth, or rather, not knowing the exact details. Bringing to life fictional characters allowed me to imagine situations and explore histories that lay beyond the direct experiences of my family. As I moved from fact to fiction, the story I was telling became something to create instead of something to report.

I had so many decisions to make. Where would I stick to fact and where would I use fiction to float the story? There were some facts that served as ballasts. These were the non-negotiables. Some were tiny details—a jade pendant, a porcelain teacup, a box of flashcards. Others were real events that had to be incorporated. But I needed to simplify. I consolidated their journey, keeping only the main cities and focusing their travel along the Yangtze River. The manuscript became a kind of parallel universe to my father’s notes; there are the lives of the real people and there are the lives of my characters and every so often those lifelines intersect. The real and the fictional share a conversation or location or physical object, and then they continue on their different ways until they cross paths again.

*

My father’s notes provided the physical journey, and my initial drafts presented a narrative journey, but the heart of the writing for me was developing the emotional journeys of the main characters. I felt that the best way to deepen the emotional journey of each character was to fictionalize true events based on my father’s stories and research into other Chinese people’s lives who shared similar patterns of migration. By reading memoirs, oral histories, and scholarship about this demographic, I built an emotional appreciation for how families lived through these difficult times. These works gave me a rich context and vocabulary for the experiences that my father’s stories only hinted at. For me, fictionalizing true events opened a scope to explore the immediate impacts as well as the longer-lasting repercussions of war and displacement on individuals, relationships and families.

Even though there was much research and writing that I had to leave out of the final manuscript, it all informed my process. Nothing is ever wasted. And nothing is ever complete; I could have researched for many more years and still found more angles, more stories, more complexity. But from the beginning of the project, there was an urgency, a sense that I had to write this story now. A sense that time was running out.

In one way, time did run out. My father, who knew I was writing a book based in a large part on his life, passed away in early 2019 while I was still drafting. Although I’m sure he would have told a different story than the one I have written, his life and his orchard inspired my book. It took me close to four years and nearly four hundred pages, but I’ve finally told the story I wanted to tell about his trees. I like to think he might be somewhere smiling a little bit to see how it turned out. As reluctant as he was to tell his own, he always did love a good story.

__________________________________

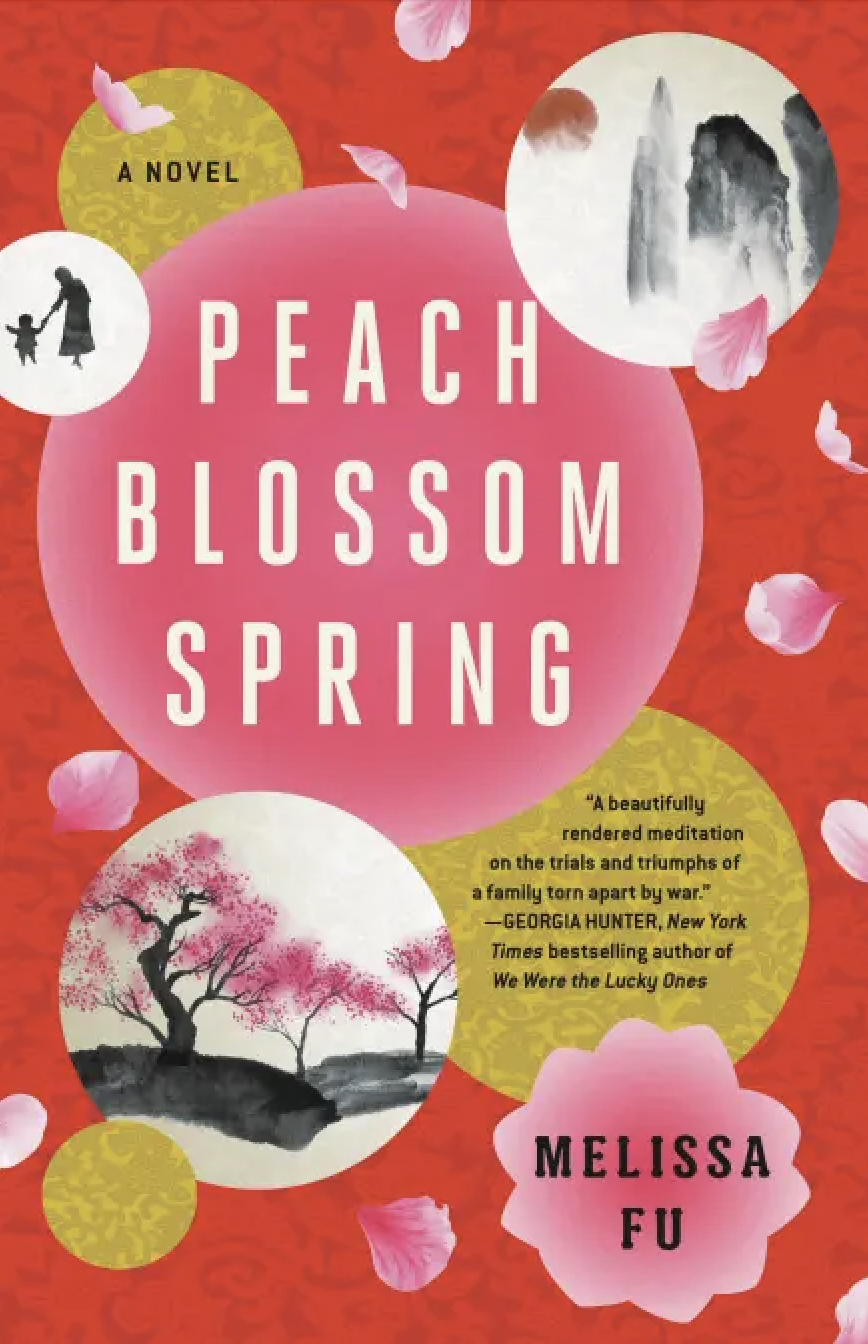

Peach Blossom Spring by Melissa Fu is available via Little Brown and Company.