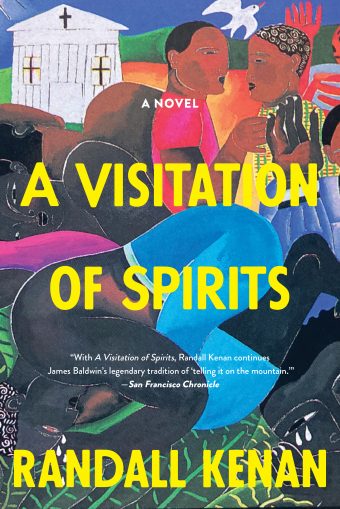

“He Gives Us Back Our Wonder.” Tarell Alvin McCraney on the Work of Randall Kenan

It begins with a fall, the time of year, from Grace.

It begins with a spell, as it must, with Horace, young, gifted, and Black, calling on all a sixteen-year-old knows of the earth, all he can remember from church, and all the ancestors whisper in dreams, to aid him in his plight to change. Horace Thomas Cross in fictional Tims Creek, North Carolina, is determined to find the strength to up and fly away; away from all that won’t understand him and that he himself does not understand.

Horace has made a self-discovery and needs to get out before anyone else uncovers it. And because A Visitation of Spirits, a story about an old family in the New World, ponders Grace and the mercurial absence of an omnipresent God, Horace’s journey leads him through sudden storms, into woods dark and familiar, and at long last, face-to-face with himself.

I don’t know if Mr. Randall Kenan meant to awaken me the way he did; startle me into self-awareness. I don’t know if he came from a family described in the book as proud and matrilineal. I don’t know if he meant for this book to be one that Black queer men of a certain age regard as “a first testament” to our lives in a waning pandemic, a will to live, a recounting.

I don’t know.

After his death in August of 2020, I sorted through my old email accounts to find our correspondences. He spoke to me like I was a nephew, he wished me well and hoped I would find peace. “Oh, take a vacation,” one email laments. I don’t know if he was saying it for me or him.

I only met him once, for tea, black for him and green for me, in a too-early cafe in midtown Manhattan. Our teatime was awkward, he allowed it to be, so that neither of us felt the tremendous pressure to be extraordinary as we often had to be in other spaces. As Cousin Ann recounts in Visitation, “But don’t you know it yet, Horace? You the Chosen Nigger.” But here, he knew, I needed, maybe we needed, to be ourselves, nothing more. He allowed deep pauses of nothing, for genuine questions to arise. He set the portrait I would come to replicate in my own work, the painting of two awkward men from the Southern United States who queerness had chosen and who, because it was the Blackest, truest thing to do, had chosen it back. We could love all the things that did not add up. We could love the quiet and the questions. We could embrace curiosity with a capital C.

“Curiosity” in this novel, Mr. Kenan assigns to Rev. James “Jimmy” Greene, the dutiful widowed pastor cousin/uncle to Horace. I don’t have to explain a cousin/uncle, right? Maybe I do. Your father’s cousin is your cousin, yes? But said cousin is your mother’s age; so, you give the respect you would of an uncle or aunt to that cousin. Right? Because . . . Because you do.

He takes us through the things we forgot in order to remind us how deeply curious we are or were about each other but more importantly about ourselves. He gives us back our wonder. True graceful wonder.Horace, who as I said before, is right as we speak, as you read, if you turn these pages, trying desperately to change himself into something—anything else—with powers we dare not speak of; with answers he has braided together from the very book cousin/uncle Jimmy sites to counter his cousin/nephew’s waxing, confusing desires. Even as Jimmy wants to make room for Horace’s exploration, he is still a pastor and parishioner, mourning his inability to allow his own curiosity to dig him deeper into the murky and unknowable mire that is life. Maybe that’s why his wife strayed? Maybe that’s why his little cousin Horace is a… He can’t even say it. “You know as well as I what the Bible says” is Jimmy’s occupational answer to Horace’s inquiry on same-sex love. For Horace, the clarity of damnation in that question still eludes his thirst for answers.

It would be something if this novel were a tome of thoughts and ideas from antiquity that save us from ourselves today. No lie, I wished it were, the twenty-year-old who first read this book sped through it and devoured it hoping its passages of longing and family misunderstandings—the quiet moments of surrender between the one you wished you could love and the one who loves you—all I hoped would be answered or explained away at the end of this book, pointing out the concise answer of “why?” But then how would Mr. Kenan get us to come back, keep us coming back? Keep us revisiting.

I have reread this book every two years (sometimes twice in a year) since 2001. I reread and I remember and sometimes I reflect. These hauntings, these revisits, are all fueled by beautiful questions Mr. Kenan gifted us and cast us not as scholars or simply readers but as the curious; it’s the reason he talks directly to us and reminds us, through monologue of gentle inquiry, what Black life in the South was like prior to the cellphone. “But you’ve seen this, haven’t you?”

It’s as if he wants us to secretly nod to each other over these quandaries heavy in our heart or gather, huddle around this story’s puzzle pieces together, finding and putting them next to each other, ultimately illuminating a work that feels foreign and all too familiar. Because there will be some, they come and they come, with questions like Horace, some will be curious like Jimmy, and even some will have questions like Aunt Ruth, the oldest living relative of Horace and Jimmy, though she makes sure they remember their kinship is through marriage, not by blood. Even she is wondering where the road turned. Some reads, you wish the characters would look around at all the gathered spirits and know that they are not alone in their questioning. We are not alone. Mr. Kenan makes sure we know it.

Indeed, he takes us through the things we forgot in order to remind us how deeply curious we are or were about each other but more importantly about ourselves. He gives us back our wonder. True graceful wonder. Wonder at a world that would deny love to a boy because he aimed it at another boy. Wonder for a town that could not keep the secret affair of a pastor’s wife from diminishing his following. Wonder for an elderly woman, mad at the world, bent on heavenly reward, finding grace and joy at a child’s game like Pac-Man. That wonder will have you back reading, feeding the fire of questions that continue to consume you, burnishing your spirit with each revisit, each time more curious with a capital C.

____________________________________

Introduction © 2022 by Tarell Alvin McCraney, excerpted from a new edition of A VISITATION OF SPIRITS © 1989 by Randall Kenan. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Inc. All Rights Reserved.