CROSS WORDS And the D-Day Invasion

I would say, with apologies to Winston Churchill, that never have so many labored so hard to obscure what was so obvious to so many as during the spring of 1944. Every school child in Europe knew that soon the allies were going to hurl themselves against the Nazi held Atlantic coast of France.

And there were only two places with beaches close enough for unlimited air support from Britain and wide enough for major military operations - the Pa de Calais, just 20 miles across the channel, and 75 miles away, in Normandy. But it was vital the 400,000 German defenders not know which of these two spots was the eventual target, or exactly when the invasion would occur. The planned date and location of the invasion was maybe the second biggest secret of the 20th century.

It would take 1 ½ million military personnel, and probably another 2 million civilians to prepare and launch the invasion. And 4 million people can not keep a secret. So, like a puzzle the invasion was divided into pieces, each given a code name to disguise how it fit into all the others.

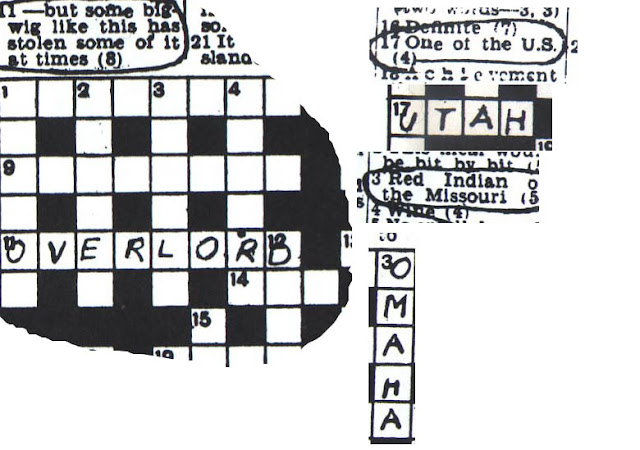

The over all plan was code named “Overlord”.

Misinformation fed to confuse the Germans was code named “Bodyguard”. Bombing to isolate the beaches was code named “Point Blank”.

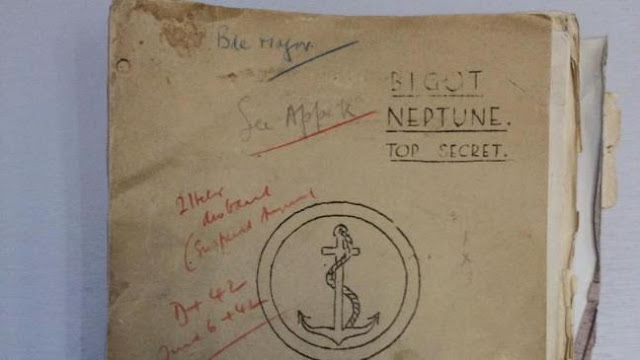

Naval operations were code named “Neptune”. Operation “Tonga” was the code name for the British parachute and glider attacks designed to be launched before dawn behind the beaches.

The British beaches were “Gold” and “Sword”, the Canadian beach “Juno”, and the American beaches “Utah” and “Omaha”.

Architectural drawings for the two floating harbors built in England and towed across the channel were code named “Mulberry”.

And the flexible gasoline pipeline rolled out and laid down under the channel after the invasion was named “Pluto”.

Out of the millions of documents generated for “Overlord” - the 9th Air Force's plan for the airborne troops parachute drop alone was 1,376 pages and weighed 10 pounds - ranged from shipping bills of lading to company rosters. Only a few thousand of these referred to the actual time and place of the invasion. But almost all of them hinted at one or both.

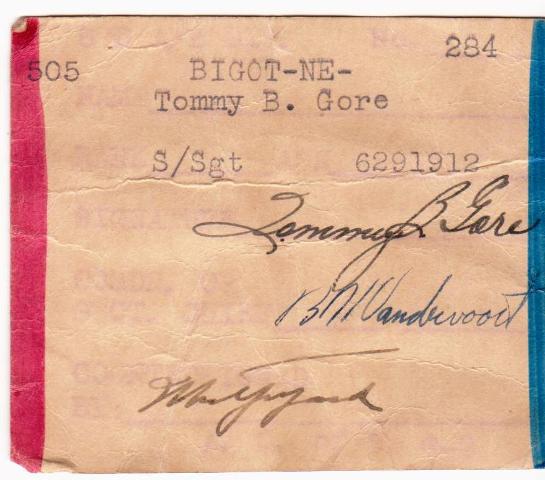

Besides being stamped with “Top Secret” and "Eyes Only", the most sensitive documents also had the word “Bigot” stamped on them. Only a few hundred people with an absolute “need to know” were allowed to handle or read “Bigot” papers. These people were given special security clearances, and were described as “Bigots or “Bigoted”.

There were, of course, slip ups. In March a U.S.sergeant accidental used “Bigot” papers as packing material for a present sent to his sister. When the package broke open in transit, workers in the Chicago Post Office were put under FBI surveillance. Some wind and an open window forced British staffers to spend two hours recovering 12 copies of a “Bigot” memo from a Whitehall street. An abandoned briefcase containing “Bigot” papers left on a train in Southern England was turned in to the station master. The last owner of those was reduced in rank and placed under detention. And several officers were reduced in rank and relieved for talking too much at a cocktail party . But the British domestic Military Intelligence Service - MI 5 - thought all these leaks had been plugged. At least until they picked up a copy of the Daily Telegraph newspaper on 2 May, 1944.

The Daily Telegraph - “The Largest, Best, and Cheapest Newspaper in the World” - started out as a penny tabloid in the 1850's. By the 1930's it had built a circulation of almost 1 million readers by assuming its audience was intelligent, middle class and progressively conservative. The Telegraph helped make Winston Churchill Prime Minister in May of 1940., and in late 1941 the paper printed an offer to donate £100 to charity for each person who could solve the paper's crossword puzzle in less than 12 minutes. Winners were then ordered to report as code breakers to Beletchley Park, home to the Twentieth Century's ultimate secret, the breaking of Germany's top secret code machines.

On that Tuesday, 2 May, 1944, a “Bigoted” officer was solving the Telegraph crossword and stumbled over the clue for 17 across - “One of the U.S. (4 letters)”

The next day the paper published the solution - “Utah” - the codename for one of the intended American invasion beaches (above).

It was most likely a coincidence. Right? Well, paranoia being an occupation hazard for intelligence officers, this hyper vigilant Bigot decided to look closer. And ominously, a review of solutions to April's crosswords turned up more invasion beach code names - “Gold”, “Sword” and “Juno”

Well, gold and sword were common crossword words, and even if Juno was unusual it was decided an investigation might draw too much attention And for ten days the Telegraph crosswords were clueless, as least as far as military intelligence was concerned.

And then on Monday, 22 May, 1944, the clue for 3 down - “Red Indian on the Missouri (5 letters) – led to the obvious solution published on Tuesday, “Omaha”. - the other intended American invasion beach (above) code name. And now that their suspicions had been aroused, in the same puzzle the word “dives” appeared, which might refer to the Normandy river named Dives, at the eastern edge of the invasion area. And also in the puzzle there was the name “Dover” which did not have any special importance to the invasion, but which, at this point just sounded suspicious. MI 5 decided to assign two agents to investigate.

It didn't seem the newspaper itself could be responsible. The owner and editor-in-chief, William Berry, was so trusted he had briefly served as the Minister of Information. But agents learned the crosswords were written ahead of time not by a Telegraph staffer, but by a 54 year old freelance “compiler”, a legendary amateur football player and “stern disciplinarian” headmaster of the Strand School for boys, Mr. Leonard Sydney Dawe (above). And the agents had questioned Dawe once before when his crosswords had seemed to violate security.

On Sunday, 17 August, 1942, a puzzle composed by Mr Dawe contained the clue “French Port (5 letters), with the answered confirmed on Monday, 18 August, by the word “Dieppe”. At 5:30 in the morning of Wednesday 19 August, 1942 (one day later) , 5,000 men from the 2nd Canadian infantry Division, 1,000 British Commandos and 500 U.S. Army Rangers landed on the stone beaches of the French harbor of “Dieppe” (above). Their objective was to seize and hold the port for 24 hours.

But the Nazis were waiting as if they had been forewarned. Less than 6 hours after landing the Canadians had suffered 50% causalities (above) and the surviving men had to be withdrawn. MI 5 had interrogated Dawe for several hours then, and come to the conclusion that the word “Dieppe” had been “a coincidence”. But as they say in the intelligence game, fool me once, shame on you, fool me twice and you are in BIG trouble.

The puzzle published on Saturday, 27 May, 1944 was the final straw. Almost as if Dawe were taunting officials one of the clues to that day's puzzle was “...some bigwig like this...”(8 letters)”, which led to the solution on Sunday, 28 May of “Overlord” - code name for the entire invasion! Leonard Dawe was arrested at the school's temporary home in Effing and brought in for questioning. As he had two years earlier, Dawe denied having any inside knowledge, and kept denying it “They turned me inside out,” he said later. “But they eventually decided not to shoot me after all.”

Meanwhile Dawe's crosswords kept indicting him. Tuesday, 30 May the clue was “This bush is the center of nursery revolutions”. The answer, printed on Wednesday 31 May was “Mulberry” - the code name for the floating artificial harbors. And then on Thursday, 1 June the clue for 15 down was “Britannia and he hold the same thing.” The solution published on 2 June was “Neptune” - code name for the naval operations within Overlord. It seemed to some that disaster was certain. But shortly after that the Daily Telegraph crossword didn't matter anymore.

Just fifteen minutes into Tuesday, 6 June, 1944 the first paratroops landed on French soil. At 5:45 in the morning the Operation Neptune bombardment began. And at 6:30 troops began landing on the American beaches of Omaha (above) and Utah . An hour later the British and Canadians followed.

By 3:00 that afternoon the first sections of a Mulberry harbor breakwater were sunk off the beaches. By nightfall, the allies had landed 156,000 men along 50 miles of Normandy coast, and penetrated up to 6 miles inland. The invasion was a success, so far..

On Wednesday, 7 June, Leonard Dawes was released by MI 5, and after reporting to the schools managing board - who were close to firing him - the first person he wanted to see was a 14 year old student named Ronald French. Having called the boy into his office, Dawe immediately, “...asked me point blank where I had got the words from. "I told him all I knew...” And what young Mr. French knew would have sent the spooks from MI 5 into a faint.

According to Roland, the school's temporary home (they had been bombed out of their original sturcture) was surrounded by Canadian and American military camps, filled with young soldiers, most no more than four or five years older than Roland, all in training for the invasion. ”I was totally obsessed about the whole thing", Roland admitted recently. "I would play truant from school to visit the camp. I used to spend evenings with them and even whole weekends...I became a sort of dogsbody about the place, running errands and even, once, driving a tank.”

He explained that the soldiers talked freely in front of him... "because I was obviously not a German spy. Hundreds of kids must have known what I knew.". Bryan Belfont, another student recalled, “The soldiers were obviously lonely...they more or less adopted us. We’d sit and chat and they’d give us chocolate.” But just how much did these children know?

“Everyone knew the outline of the invasion plan and they knew the code words”, said Roland. “Omaha and Utah were the beaches, and these men knew the names but not the locations. We all knew the nickname for the operation was Overlord....Hundreds of kids must have known what I knew.” As proof Roland showed Dawes the composition books he had filled with diary like notes. According to Roland, Mr. Dawe “was horrified and said the books must be burned at once.” And while the book burned, Dawes lectured the boy on national security, and war time censorship. “He made me swear on the Bible I would tell no one about it.” Roland was so traumatized he stopped doing all crossword puzzles, himself.

So there was the great leak, the hole in the allied security net. Thousand of young soldiers talking to other young soldiers, overheard by even younger boys. It was to be expected. It was even allowed for. Knowing the code words would tell the Germans almost nothing essential. But after 6 June 1944 the invasion was no longer a great secret. Why did Leonard Dawe insist the boy swear never to reveal the details? The answer was that Dawes was protecting his own “Butt” (1 down, 3 letters) . Because Leonard Dawes was a bit of an “ass” (1 across, 3 letters).

Dawes had created more than 5,000 crosswords for the Telegraph since 1925, and over the following decade had stumbled upon the easiest working method. He would lay out the crossword grid on a sheet of paper pinned to his wall. There were no letters or numbers in the grid, just empty squares with some blacked out for random aesthetics. And he would then invite his students to fill in the blocks, telling them it was a to improve their “mental discipline”. In truth it was to improve his income. Dawes would then write clues to match the words provided by his 14 and 15 year old wordsmiths. In their naivety they considered him “...a man of extremely high principle.” But if the truth had come out the newspaper would have fired him for plagiary, and the school for lying.

Leonard Sydney Dawe died in January of 1963. But Roland French, like the other adolescent wordsmiths, kept his school master's secret for another two decades, finally revealing the truth in an interview in 1984. And only then did Roland French feel he could start enjoying solving crossword puzzles again.