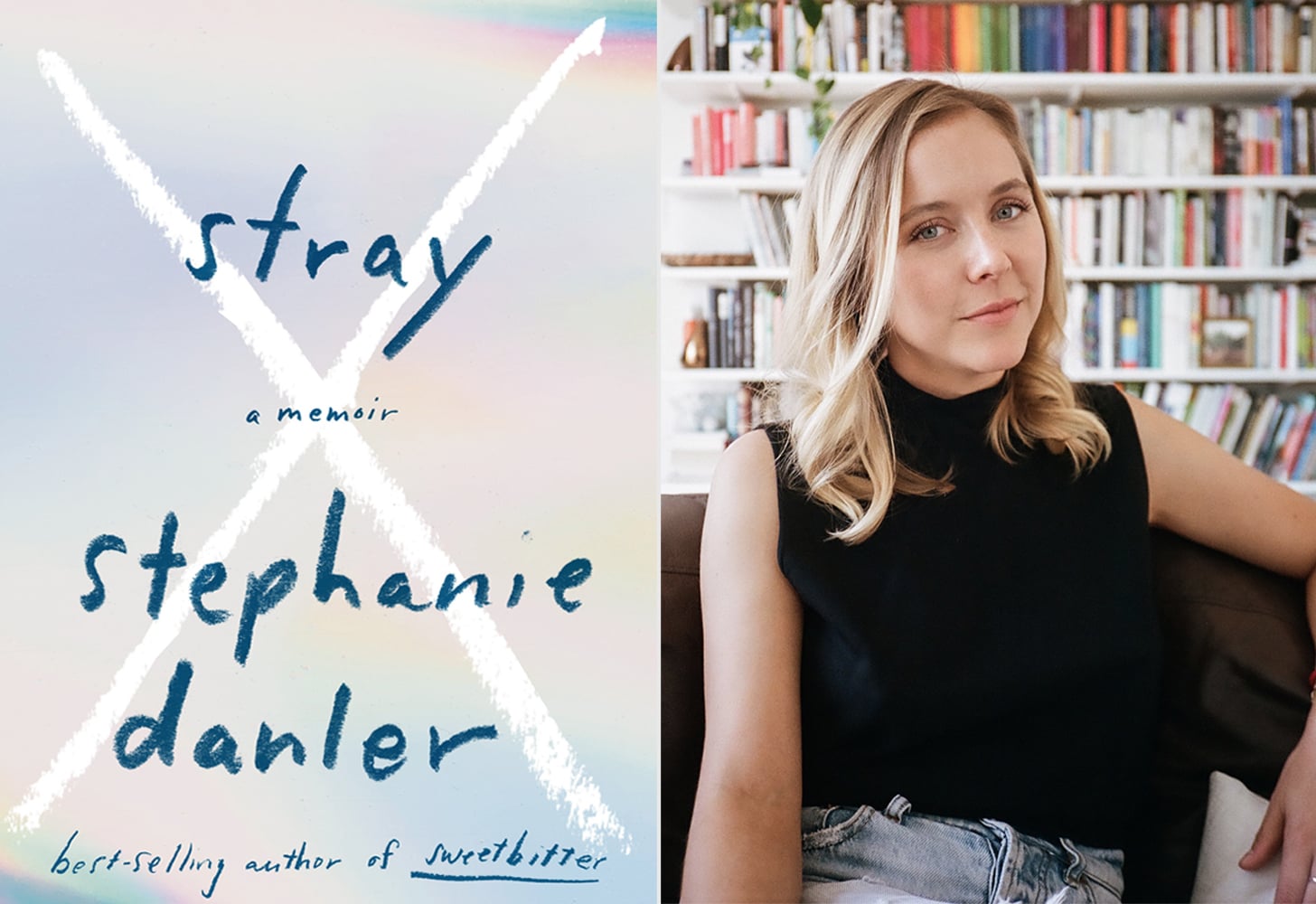

Charmed: An Interview with Stephanie Danler

To call Stephanie Danler generous would be an understatement. Before we ever met, she read an advance copy of my memoir and posted about it on her Instagram account. For this fledgling author, it felt like the equivalent of being on a late-night talk show. Thinking it was a shot in the dark, I asked if she would be in conversation with me for an event at McNally Jackson in Williamsburg. At that time, in 2018, Danler lived six months out of the year in Los Angeles and six months in New York. She was in production on the second season of the television adaptation of her best-selling novel, Sweetbitter, and six months pregnant with her first child. And yet, she said yes.

I had heard about Sweetbitter, but I hadn’t yet read it. Its publishing story is mythical: the waitress who hands her manuscript to someone at Knopf and gets a book deal. I’d seen the wine glass on the cover, the bestseller status, and somehow reading it didn’t feel urgent. Really, I was jealous. I assumed I knew something about Danler’s life. It seemed charmed.

I read Sweetbitter and realized it had earned every bit of praise it received. It is a work of careful and keen observation, full of yearning, and satisfying in an almost gastronomical way.

Then I read a precursor to her memoir, Stray—a heartbreaking and lucid essay called “Stone Fruits,” which appeared in The Sewanee Review. In it, Danler reckons with her abusive mother, now disabled from a brain aneurysm, and her drug-addicted and largely absentee father. Any notion of her life being charmed was demolished.

Or was it? I had always thought charmed meant easy or without friction. But really to charm is “to control or achieve by or as if by magic,” and Danler’s prose has a sorcerer’s prowess and a wisdom that borders on mystical. The writer and witch Amanda Yates Garcia says that each initiation we face can teach us what our magical powers are and what gifts we have to offer the world. Danler offers beauty and hope in the redemptive powers of writing. Her gifts lie in her willingness to share some of the most intimate and painful parts of her life.

This interview was conducted over the phone in late April, while both of us were quarantined at home.

INTERVIEWER

A lot of people have called your first book, Sweetbitter, an autobiographical novel. And yet, though you obviously drew on your own experiences to write that book, it is not quite autobiographical. Why did you choose to write Stray as memoir?

DANLER

I’m generally not concerned with genre. As a reader, I don’t care how factual a novel is or how fallible a memoir is. But when I started to write about people I love, who are still alive, it became important to me that I held onto the truth as much as possible. It’s my truth, so it’s subjective, but I think if you are going to say that your mother hit you, or your father overdosed, or that your lover treated you cruelly, you owe it to the people involved—whether they like it or not is a different story—to tell the truth. I wanted several times to turn it into a novel because the idea of hiding behind something was so appealing. Controlling the story when you’re writing fiction can be such a relief, especially when you’re dealing with the unruliness of real life, which doesn’t conform to a narrative arc. I think I struggled with Stray for so long because I didn’t have a big ending and I thought memoirs demanded real turning points. For Sweetbitter I had an ending because it was invented. I thought, Oh, this is the swelling of the symphony that marks the end of our journey. With the memoir, I could have ended in a thousand different places. It’s really about that ongoing-ness of living. I would have loved to just disguise myself and not feel so raw about it. But I do think it’s important for readers to know that it’s true.

INTERVIEWER

I don’t know if you outline or not, but did not knowing the ending hinder you as you began to write? Or were you writing because you were trying to figure something out?

DANLER

I was collecting pieces for such a long time that it became a kind of outline. But I could not actually write the book until I knew the shape of the entire story, which included the ending. In the meantime, I was able to research California, continue examining my past, collect memories, talk to family members. I wrote the first draft of this book in nine weeks from start to finish, but at that point I had hundreds of note cards. They had been tacked up in fifty different arrangements and many of the passages had already been written, so I had a very clear sense of where I was going. I also couldn’t write it until I figured out the present tense story line for Stray, which is moving back to California and being embattled in a love affair. I wanted the narrator to be speaking from a clear place.

INTERVIEWER

There are two romantic relationships in the book. There is The Monster, a married man with whom you’re having an affair, and The Love Interest, with whom you are slowly falling in love (and who you later marry.) At one point, The Love Interest seems worried about the way you seek drama and asks, “You can’t write if there isn’t conflict?” Was it more difficult to write about your relationship with him since it’s less “dramatic” than your relationship with The Monster?

DANLER

In a way it was easier. When I was very slowly falling in love with The Love Interest, I didn’t trust the depth of a relationship that felt good or easy or “healthy,” which is a word that I hate when it’s applied to relationships. It’s too virtuous. It’s gross. You want to do something devious when you hear that. I had a really hard time believing my relationship with The Love Interest could sustain me or interest me. But that’s conflict, that distrust. That’s something to write about. Writing about The Monster was really difficult—to remember how deeply in love we were. There was something very pure and electric and life-altering about the way we felt toward each other. We were willing to risk so much to try, and we kept trying, we couldn’t let it go. I think that my adolescent value system is still enamored with that kind of love. Where you’re powerless, you have no control, you submit yourself over and over again. You fetishize the pain. It’s so different from the kind of love that I am experiencing now in my life with my husband. And so, to inhabit both … to go from my office, reading, you know, a ten-thousand-word sexting WhatsApp transcript from five years ago, to then walk out and to see my husband, to nurse my child, I actually felt like I was going crazy. It was a very beautiful time, while I was writing Stray, but it took me hours to recover myself at the end of the day. And, you know, you don’t have hours when you’re a writer and you have a newborn.

INTERVIEWER

I completely relate to that. At what point did you share what you were writing with the people you were writing about? I remember my own process when I published a memoir, how each person had different needs. How did you tackle that?

DANLER

It’s so complicated, and it shocked me how fraught the whole process was. To be perfectly honest, I didn’t think about it at all when I was writing. The very first draft of Stray had things that I never had any intention of publishing, but I had needed to write them out. I am good at blacking out the rest of the world when I’m really focused on a project. I don’t think about audience, I don’t think about marketing. I don’t think about my own shame. I don’t think about how I’m portraying people. It’s a very narcissistic bubble, but it’s what I need to write. The same was true with Sweetbitter, I did a lot of correcting after the fact as I took in all of these other factors. With Stray, those factors were amplified by the real people involved. I really didn’t want my parents involved, not that my mother could be. But there’s another kind of more investigative memoir—Dani Shapiro’s Inheritance comes to mind—where there’s an absence and you search for the answers. And through that search, you’re put on a journey. I thought about calling my aunts and uncles and my cousins and conducting interviews and tracking down my mom’s old boyfriends, who I vaguely remember from my childhood, but at the end of the day, I wasn’t interested in that. I was interested in the absence and the mark it left on me. I didn’t want to necessarily put the puzzle pieces together with my parents and say who they are. All I could really say was how they affected me. They still haven’t read it. My mom doesn’t read, because of her brain aneurysm, so it’s less of an issue. I assume my father will read it at some point. But everyone else in the book, I gave them a manuscript. And as you mentioned in your question, for some of them I said, “If you have an issue with anything, I will change it.” And then to some of them I said, “If you’d like your name changed, I’m happy to do that.”

INTERVIEWER

What were some of the reactions?

DANLER

The most important people were my sister and my aunt, who were both very supportive … but the first time my sister read a handful of pages from the mother section, she said, “That didn’t happen.” She was referring to when I moved home in the summer of 2005 to nurse my mother when she was released from the hospital. My sister said, “I was her nurse.” And I said, “What are you talking about? I left my job in New York. I had an apartment lined up. I came home. I worked five days a week.” And as we talked through it… I mean, the shock on each of our faces. I thought, This is a rupture. Like, one of us has brain damage. And we’re not going to be able to move past this conversation because our memories are so wildly different from each other. She believes that she nursed my mother. I believe that I was a nurse for a period of time that left its mark on me and was frankly horrifying to my twenty-year-old self. And what we came to is that I left California after three months of care. I went back to Ohio, I finished college and moved to New York. My sister lived with my mom for the next two years.

INTERVIEWER

Oh, wow.

DANLER

And while those three months had such an impact on me, to my sister they were a blip in the amount of care that she ended up giving. Her story is that I got to be free. And my story is that I have been exiled from their family life. That kind of disagreement only makes the book better, if you can come to an agreement at the end of it. But it’s a reminder that memoir is remembered experience. It is not journalistic fact. One person says it was night and the other says it was day, and they’re both sure of themselves.

INTERVIEWER

In Sweetbitter, your narrator is affectionately called Baby Monster by her restaurant colleagues. In this book, you call the married man you’re having an affair with The Monster. Tell me a little more about this word, monster, and its importance to you.

DANLER

For me it’s an affectionate term for people prone to living in extremes, people with outsized appetites, oftentimes narcissistic, lonely people. In Stray it’s more of the Nietzschean monster—“If you gaze too long into the abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” If you spend enough time around monsters you will become them. I think readers expect that the third section will be about this man whom I call The Monster. Really, it is about an epiphany during this affair, that I’m doing this to myself. I’ve continued to chase a married man whom I can’t trust, who has made it clear time and time again that he’s not able to leave his wife. As for who’s causing the damage, and who’s causing the pain, it’s me. I am the monster. I think without that realization, which took me an embarrassingly long time to come to, I would not have been able to stop. Taking responsibility allowed me the control that I felt like I didn’t have for years, frankly. It moved me out of being a victim. To me, that’s end of the book. The recognition and the small call to action. That is a profound shift for someone who has been walking in circles for a very, very long time.

INTERVIEWER

One of the things that I have enjoyed so much in our personal conversations is talking about work and money. In Stray you write, “I have always found solace in work, real mind-blunting labor.” You talk about unpacking books at Borders, working at coffee shops and restaurants. How long has it been since you’ve just been writing and not doing any other side job? And how has not having a side job affected how you write?

DANLER

First of all, I also appreciate our conversations about money and making a living as a writer. I feel like we’re in desperate need of transparency about those things, but they’re considered so inappropriate.

INTERVIEWER

I know! I keep thinking, Okay, I’ve written a memoir about sex and love, I guess the only place I have to go now is money.

DANLER

Right. Money is the only thing we don’t talk about. And it runs my life. I wish I could say that I am motivated by a divine vocation or an uncontaminated love of art. I do believe that art is separate from capital, but for me personally, I can’t afford to separate them. It’s been five years since I worked in restaurants, but that sense of desperation that I had, of needing to make ends meet, of being so close to a zero balance, is still with me. All of it is. Even when I was a manager and wasn’t working for tips, that adrenalized sense of service and performance and long nights… I’ve never lost it. And so, “just writing,” as you know, means writing for magazines, writing for websites, writing for television if you can make it work. Since Sweetbitter, I’ve written interviews, freelance essays, presentations, speeches, articles, television scripts. I hadn’t written a book in four years but I was writing constantly. Writing full-time is the craziest privilege I’ve ever encountered in my life. That, to me, is winning the lottery. At the same time, I think I imagined that if I ever made it to that point, that it would be a life of contemplation.

INTERVIEWER

(Laughs.)

DANLER

That it would be a life lived purely for books and I’d constantly be in conversation with writers who were dead and alive, whether at residencies or while traveling. All I’m trying to say is that it’s still real life with rent to pay and panic and student loans and severe budgets and good years and bad years, dependents, emergencies. It has not provided the ease I thought it would. Does that make sense?

INTERVIEWER

Absolutely. So, where do you find solace now if not in the mind-blunting labor that gave you solace before?

DANLER

I actually find it in the busy work, the emailing, the chasing of TV projects. These years with Sweetbitter have been such a roller coaster. When I moved to California right before Sweetbitter came out, there were four months when I didn’t know what was going to happen. No one needed me. No one emailed me. I didn’t have to wear an apron. I used to watch the light change. I would sit in bed and be reading or working, and look out the window and then notice, Oh, an hour has passed. There was a week when I decided I wanted to microdose mushrooms while I wrote. Some days I’d get a little high and some days I wouldn’t. Now that I have my son, I cannot remember what it was like to have that kind of time. Now, my whole life feels like mind-blunting work. I still have to clean up the house after we get off the phone.

INTERVIEWER

The first house you rented when you moved back to LA during that period had been occupied by Fleetwood Mac during the Rumours era. You’re very enamored of this fact but other people don’t seem to believe it or care. I wanted to hear a little more about your love of Fleetwood Mac and what it meant to you to have that shared place with them.

DANLER

I’ve had that love since childhood. I don’t know anyone who wasn’t obsessed with Fleetwood Mac at that age. If you’re a young woman who thinks they might be a writer, Stevie Nicks is probably one of your first patron saints.

INTERVIEWER

True.

DANLER

Stevie Nicks, then Sylvia Plath, then Joan Didion. Or in some altered order. But as far as what it means to the book, Fleetwood Mac is the fantasy of Los Angeles that you’re sold when you’re from elsewhere. You’re going come to LA, make art, live in Laurel Canyon, and things will be bohemian and easy and glamorous. But that house I lived in was falling off of the hillside. I mean, I ended up having to leave. I should have added that in the postscript because the landslides became constant. The landlord took out the eucalyptus. The entire half of the hill had fallen into the house. I couldn’t sleep when it was raining, I was terrified. The contrast between the way that people romanticize California and what it really feels like to live in such a volatile environment is what I was interested in with Stray.

INTERVIEWER

Did you already have a book deal? Were you were supposed to be writing a memoir?

DANLER

I had a two-book deal with Knopf when they bought Sweetbitter, and I had sold them a second book that was a novel. When I moved to California, I told my editor I was moving there to start the book. I never wrote a word of it. I researched heavily. I went to Egypt for a month on my own dime, to research. The whole trip was a failure. The idea for that book was based on an idea of the kind of writer I wanted to be. It never felt urgent. I also carried the biases about memoir that a lot of people do, especially those who have studied fiction for most of their lives. It took two years before I told Knopf that I was writing something personal. Which is exactly what I said. “I’m writing personal stories.” And my editor said, “Like a memoir?” I said, “Oh, my god. No. Never! It’s just personal writing.” It took another year to admit it was a memoir. Knopf was great about it. But I will say, it was a lot of blind faith. Peter, my editor, had not seen a single page of it until I turned in the first draft.

INTERVIEWER

Oh, wow.

DANLER

I had been writing nonfiction for The Sewanee Review and a few other places, so I think he knew I could write nonfiction, but as I was sending in the first draft I thought, Jesus, I hope this works. It had been four years at that point.

INTERVIEWER

You describe your father’s addiction as a black hole behind his heart that drugs merely pacify. You say that you inherited that black hole from him, and I wondered if writing is what pacifies it for you.

DANLER

We’re taught that if it’s literary writing, it’s not therapy, but just the act of writing is deeply therapeutic. There’s so much research on that. I do think writing keeps me grounded to a truth outside of my own emotions. It’s almost Buddhist in the way it causes me to witness my life. I think the ability to create that distance in moments of serious pain has probably saved my life on many, many occasions. I also like drugs, I also like sex, I also like travel. So, it’s not that I have only this one, virtuous coping mechanism.

INTERVIEWER

Okay, phew.

DANLER

But writing has saved me from ever going too far. It’s always pulled me back from the edge. When people used to assume that Sweetbitter was autobiographical, I would say, But I moved to New York to be a writer! I got that job in restaurants to write. No matter how late I stayed up, or how many mistakes I made, or how terribly I embarrassed myself, I had a separate life from the restaurant world. Without that, I don’t know. I don’t know that I would have made it.

Leah Dieterich is the author of the memoir Vanishing Twins: A Marriage (Softskull, 2018). Her essays and short fiction have been featured in Lenny Letter, LitHub, Buzzfeed, BOMB Magazine, and elsewhere. She lives in Portland, Oregon.