an ode to my moleskine

The first journal I remember writing in was a black, wide-ruled, spiral-bound notebook. I was in first grade, and had somehow associated keeping a journal with being mature, so I started to write about what happened to me every day: notable moments in school, who I played with on the weekends. By 3rd grade, I’d upgraded to a pink book with a little brass lock to keep out all the riff-raff. (I had no siblings, and I doubt I wrote anything in there I wouldn’t want my parents to know, besides maybe who I had a crush on, so I’m not sure why I was so concerned about privacy.) You can tell my middle school journals by the colorful gel pens I used, my letters becoming loopier to imitate the cool girls’ handwriting. By high school, I’d filled countless notebooks with my idle musings and doodles. I decorated my journals’ covers with magazine clippings, photos of my friends, inside jokes. I carried them everywhere, furiously scribbling in them during study hall, chemistry, French class.

Then, the internet happened. I set up shop on LiveJournal, then DeadJournal, and a little-known LiveJournal clone called Caleida. For the first time, I wasn’t just writing for myself; I was writing to an audience. Mostly, my readers were friends from school or summer camp, but I ended up making some friends on the site who I still only know from the LJ era. LiveJournal died; we all moved on to Tumblr. I made friends there, too, some of whom are now professional writers. Somewhere along the way, I stopped journaling for me, and started writing words for a living.

I didn’t think anything of it until I read Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way. A younger me would’ve sworn it off as too woo-woo, not “evidence-based,” but in the middle of a creative rut, I followed her advice more carefully than any physical regimen I’d ever been prescribed. (Sorry, physical therapists: I almost never follow through on doing the preventative exercises I know will be good for me.) I took myself on artist’s dates to the bookshop and to the bay, and I allowed myself the joy of scooping up a monkey puzzle tree branch to sit in my office, just for the fun of it. Perhaps most importantly, I started doing Cameron’s vaunted “morning pages.” For the uninitiated, this is just journaling, but with a few rules: it must be first thing, it must be longhand, and it does not have to be good.

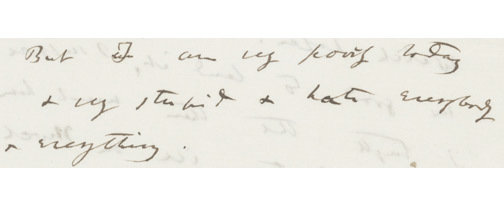

I am here to sing the praises of the morning pages. There are studies, I know, of why this is an effective practice, but I offer you no statistics, and no guarantees. All I know is that now that I’ve returned to journalling, I am kicking myself for abandoning it for so many years. It feels like those will be the “dark years,” full of stray thoughts and fleeting moments forgotten, unless I happened to take a photo of what was going on at the time. The ability to go back and read what I’ve written in past years is so calming, now that I know how everything turned out: it was all fine. And the routine of writing each morning with the same pen in the same corner with the same mug of coffee adds a comforting predictability to my day, a place I know I can process whatever happened yesterday, or in my dreams. I can sort out the detritus floating around in my head before I sit down and try to do anything, and I can get to the root of what is really bugging me by writing brutal, ugly words I know (or at least hope) no one will read but me — and I will always understand.