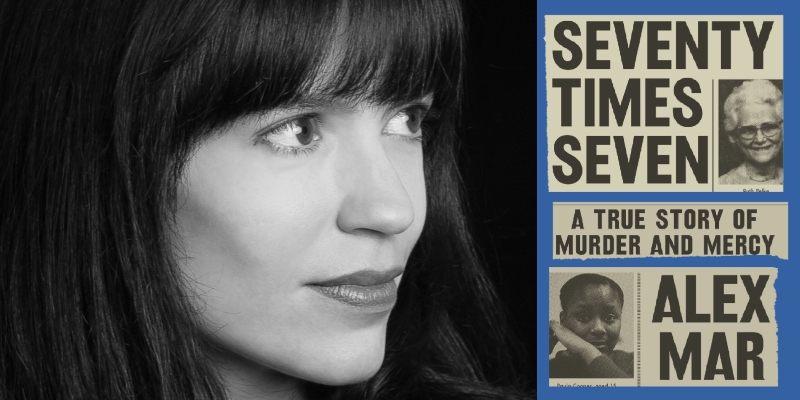

Alex Mar on the Story of Radical Forgiveness Behind Her New Book

This week on The Maris Review, Alex Mar joins Maris Kreizman to discuss her new book, Seventy Times Seven: A True Story of Murder and Mercy, out now from Penguin Press.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

From the conversation:

AM: Five or six years ago, I started doing some research into violent crimes committed specifically by women. I was just curious what kind of patterns one might find there. The percentage of women who commit violent crimes is just radically smaller than the number of men who do the same. It’s one of those ways in which a gender divide actually plays out in reality.

So along the way, In looking at maybe about a thousand different case summaries, I stumbled across Ruth Pelke’s murder and learned that this young girl, Paula Cooper, who was only 15 years old at the time, had committed this crime during a sort of robbery gone wrong. It was a brutal murder at this woman’s home. I was so struck by her age; I couldn’t really get over that. I was struck by the fact that she was sentenced to death for something she’d done at 15.

A few months later, the victim’s grandson chooses to forgive Paula publicly against the wishes of his family, his community, his coworkers, his congregation. I mean, he was a loner in coming out in support of Paula and trying to get her off of death row. I’d never heard of anything like that happening before. Since then, I’ve met a number of people in person through researching the book who’ve made that choice, but it seemed so radical. And I wanted to figure out what on earth that was all about.

MK: You talk about Bill Pelke’s moment of realization as like a religious revelation, basically.

AM: Yeah. So what’s so fascinating about Bill to me as a character so to speak, is when this murder occurred, he was an Indiana boy, grew up in an Indiana steel family. His father was a foreman at one of the mills. He started working at 19 at another of the steel mills. He went to Vietnam, he came back, he went back to work at the mill. He had no personal politics. He had no identity around making statements in public. He was a union guy. He went to work, he went home. And when this happened within a few months, he had kind of an emotional meltdown.

A lot of things in his personal life were not going well. And he was up in the crane that he operated at the steel mill during the late shift that he’d been called in for, and he just started weeping. He was alone on the shift, had nothing to do, and just kind of collapsed and started connecting all the things that were going wrong in his life. All of the ways in which he felt he disappointed by his family with his grandmother’s death. And he thought, we’re going to let her down in this way too. We’re gonna let her down if we let the state execute this girl in her name.

And so he reaches out. He writes a letter on printer paper he takes from the foreman’s office and mails it to death row in Indianapolis. And I just couldn’t believe it. I just thought that was such a fraught, fascinating choice to make. And here you have this nearly 40-year-old white man sitting in the steel mill handwriting this letter to this teenage black girl from Gary who’s on death row.

They had nothing in common except the fact of this crime. And then they really started to embark on a genuine relationship. And I just had to find out more about what that dynamic was. What on earth were they talking about? How real was that bond?

MK: This is a mild spoiler, but I think it’ll be okay. By the end of the book you talk about his relationship with Paula’s older sister Rhonda, who was a little bit more skeptical of this middle-aged man who starts up a friendship with her younger sister who’s on death row. And the idea that you have to be wary about taking part in someone else’s life transformation, playing a role in that. And you do cover both sides so compassionately and generously,

AM: Oh, thank you. That was something that was really important to me, to try to speak to and understand as many people as possible. I wanted to make sure to really understand this single event from as many angles as possible. And Rhonda in particular was so important to me in terms of just trying to have that conversation and connect with her. But it was also a really delicate situation.

If you can imagine, her sister was 15 when she committed this terrible murder. Rhonda was 18 or 19. She was in a total state of shock realizing what was going on for her sister. She had no idea how this could have happened. She didn’t see her sister as this violent person. She didn’t have a violent track record. And in choosing to stand up for her sister, she was rejected by everyone she knew. Friends.

She had a sort of makeshift family at the church she was baptized at—they froze her out. That was it. The press hounded her, she received racist death threats. It was a very bad scene. And she refused to abandon her sister. They remained in such a close relationship throughout their lives. Rhonda still calls Paula the love of her life.

I was really wary of her feeling like I was hounding her, trying to have a conversation about this incredibly traumatic time in her life. With a book there is this element of time being on your side, versus being a newspaper reporter on a deadline. And so for about three years, I just waited. I put out feelers to mutual friends. I tried to get a sense of how she was doing. And finally, one day someone said to me, I think she’s doing pretty well right now and might be open to just saying hi to you, feeling you out.

And so she became this incredible missing piece of the puzzle because she was able to tell me what it was like growing up with Paula, tell me about their relationship, even through those long years of her being on death row and in prison. And that gave me the ability to create a portrait of Paula as a girl so that you can meet her at the beginning of the book before these terrible events happen and have some kind of way of relating to her as a human being.

To go back to what you’re saying about the relationship between Bill and Rhonda, Rhonda had the same reaction that I think most readers would have to the idea of someone from a victim’s family suddenly saying oh, you know what? We should all become friends. This is not typical behavior, and it certainly goes against everything about how our justice system is structured. The prosecutor keeps these sides apart. It doesn’t benefit a prosecutor to have the victim’s family wanting to reach across the aisle. It complicates things.

So there’s this great moment that I described where Bill has written to Paula’s grandfather and said I’d love to visit with you, get to know you. I’ve forgiven Paula. And Rhonda just says, are you kidding me? That sounds insane. I’m taking no part in this. What are you talking about? I think that’s a very human reaction. Also, Gary historically has a very strong Black community and dealt with a lot of tensions around almost Jim Crow South–level segregation over the years. So an older white guy reaching across the aisle was particularly suspect.

*

Recommended Reading:

Take What You Need by Idra Novey • The Executioner’s Song by Norman Mailer

__________________________________

Alex Mar is the author of Witches of America, which was a New York Times Notable Book and Editors’ Pick. She has been a finalist for the National Magazine Award in Feature Writing, and she is the director of the feature-length documentary American Mystic. She lives in the Hudson Valley and New York City. Her latest book is called Seventy Times Seven.