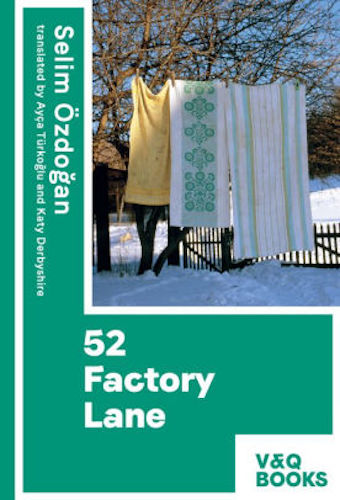

52 Factory Lane

Fuat pushes the trolly, and Gül calls out to the girls to tell them what to get as she picks tins and boxes and jars off the shelves. It’s the same every Saturday. Fuat gets up as early as possible—no matter which shift he’s just worked or how much he drank the night before, no matter how much it feels like his head’s about to crack open—but somehow, they still never manage to set off early enough to avoid a rush at the end.

Saturday is the day of the big weekly shop; they go to the supermarket and to the Turkish butcher and greengrocer, which sells almost everything now: aubergines, garlic, watermelons, bulgur, cumin, pine nuts, citric acid, okra, pepper paste, sheep’s cheese, Turkish delight. But Gül can get all these things on her own during the week. The supermarket has Coke and lemonade, pasta, flour, rice, whisky, toilet paper, washing powder, washing up liquid, cream cheese, Nutella, underpants and socks. Ceyda and Ceren are allowed to pick books from the children’s aisle, and sometimes toys too. Ceyda likes crime stories about murderous old women, terrifying thuggish men and unprepossessing but clever young detectives, while Ceren reads stories about young girls and their dreams, about worlds full of ponies and daring getaways, which she thinks are something all little German girls can have. Gül lets Ceyda pick first, because Gesine has almost a whole bookcase full at home; Ceren likes to read a book as soon as Gesine’s finished it, imagining herself and Gesine between its pages.

They buy biscuits, sweets, snacks, spice mixes, breadcrumbs, cream, sugar—Gül’s list is long, and the shopping trolley is over-flowing by the time they reach the till. Fuat is more or less irritable depending on the day, but they’re all impatient. The queue for the tills is always too long, the checkout girl too slow, time too short.

Fuat has a comment at the ready for any driver who threatens to hold them up on the way home: ‘Oi mate, I can see from your shirt collar that you can’t tell your driving license from your ID card; the accelerator’s on the right, mate, this isn’t a cinema, you’re not here to sit and watch. I could cut my toenails in the time it’s taking him to change gear.’

Every traffic light seems to linger a little longer on red, and every Saturday they have less than five minutes to go as they turn into their still-untarmacked street. Fuat parks outside the house and heads straight in; the television needs at least a minute to warm up. Gül and the girls carry the shopping into the kitchen, but they don’t unpack it. It’s Saturday afternoon, Nachbarn in Europa is on, and they never miss it.

More precisely, they never miss the Turkish part of the program, Türkiye’den mektup, Letters from Turkey. Every Saturday the four of them sit down to watch Neighbours in Europe for twenty minutes, and except for the occasional murmur of It beggars belief, none of them says a word.

It’s the only time in the week when the four of them sit together on the sofa, Fuat in the left corner, Gül next to him, Ceren cuddled up to her mum, and Ceyda on the right, always looking a little indifferent. What does she care if the news is on?

But she also enjoys these moments when the television seems to be speaking just to them, and it’s only partly to do with the language being spoken.

Week after week, the family spends those twenty minutes sitting together. If there’s been a fight beforehand, there’ll be a truce; no one manages to stay grumpy for the duration of the program. If one of them is in pain, they’ll simply forget; all cares shift to make room for the pictures and voices on the TV.

If someone were to ask her afterward, Gül wouldn’t be able to tell them what she’s just watched. Most of the time she doesn’t remember all that much; she simply sits there and breathes in the peace, the quiet that settles at the sound of the words. It’s as though the rhythm and melody of her ancestors’ language bring love into her living room, a love and connection to the rich soil of Anatolia; as though its brown earth is transported into the room along with the sounds, the scent of acacia trees and burnt cow manure, even if they only show pictures of Ankara and Istanbul, pictures of concrete and suits and uniforms worn by men you can hardly tell apart.

To Gül, it’s like spending twenty minutes on an island of her childhood, a country that is lost forever to all of us but that will never disappear. Life seems lighter once the twenty minutes are over, and though the mountain of work towers over them, it’s just a hill on an island they can never be banished from. For these twenty minutes on a Saturday afternoon, the whole family is one; they belong together. It’s a time of harmony.

Did I ever see my father and my mother together like this? Gül wonders to herself. When did we ever sit together, except to eat? Thanks, thanks be to the Lord.

This man might drink, he might gamble and wish he had a slimmer wife, but we’re a family and we have a home—who would destroy a home of their own free will?

You can’t destroy a good home. So say the ancestors. In this unpredictable world, it’s important to have a roof over your head, one you can retreat into, be it only on the sofa, in front of the TV.

Gül doesn’t sing. She doesn’t even hum, but you can imagine her singing as she cooks the dinner after the program, her daughters lending a hand. On Saturdays the sun shines inside this house. On Saturdays the sun shines all over Factory Lane, all year round, even during that time of year they all call “winter.” The summers are only brief; the time between two car journeys that seem to last forever.

It’s Saturday morning. Fuat is still asleep when Ceyda comes in the kitchen, where Gül is making the topping for lahmacun. Saniye, Yılmaz and Sevgi are coming for dinner; Gül has already made the potato salad, and all she has to do after Nachbarn in Europa is knead the dough. She’s got everything under control, but just the way Ceyda walks in is enough to make Gül lose her composure. Her stiff footsteps and their rhythm, a tell-tale sign that she’s done something bad, and the way she simply stops and waits mutely until her mother asks: “What’s up? It can’t be that bad, can it?”

“I… I’ve broken the aerial. We were playing in the living room. I ran into it and it broke.”

Gül goes to the sink to wash her hands; she feels like she’ll be able to think better with clean hands. When and how is she going to tell Fuat?

“Don’t worry, we’ll sort it out. Have you turned the telly on?”

“Yes, but it’s all blurry.”

Should she tell him before they go shopping? If she does, he’ll rant and rave all the way round the shops. But maybe they can get a new aerial there.

“Let’s have a look.”

The two of them leave the kitchen together, but before they get through the doorway, Gül senses something’s not right. She senses it the way she dreamed Ceren was drowning. She senses it the way she’ll guess in a few years’ time that Ceyda is afraid of losing her mind, even though they’ll be many miles apart by then. She senses it—it doesn’t take skill or talent; feelings and connection are gifts from God.

“Who was it?” she asks in the living room.

“Me,” Ceyda answers.

The aerial has been ripped off the TV and is broken in two. “How did it happen?”

“Ceren and I were playing around, jumping on the sofa and chairs, and then I thought I was falling, so I just grabbed hold of something.”

“Tell me the truth,” Gül says. “You know you’ve always got to tell the truth. We’re good people, we don’t lie.”

Ceyda looks down at the floor.

When should I tell him? Gül wonders again. Or might I be able to mend it? No, no it doesn’t look like it.

“The truth, my darling—there’s no need to be scared.”

She knows Ceyda is lying, but she doesn’t know what really happened.

“It was Ceren. We were playing chase, and she… She was scared of Dad, so I said I’d take the blame.”

How naive Gül is not to have thought of that herself. Feelings and connection might be God’s gifts, but other minds work better than hers.

“Go and get her. She doesn’t have to be scared.”

Not much later, the three of them are sitting in the living room. The picture on the television is reminiscent of ants marching through snow.

“What are we going to do?” Ceren asks.

“Don’t be afraid, we’ll work it out.”

“What’s Dad going to do to Ceyda when he finds out?”

“Nothing,” Gül says. “He won’t do a thing. If anyone’s going to take the blame, it’ll be me. I’ll say it happened while I was cleaning. You don’t know anything about it, alright? I just don’t want you two lying to me again, okay? You might not tell me everything; you might even lie so as not to hurt someone’s feelings, but I don’t want either of you two lying to me, and I don’t want you lying just for your own sake. Now go to your room and stop worrying about it. We got by without Letters from Turkey before.”

“But you’ll be lying to Dad,” Ceyda says.

Gül looks at her daughter; it takes her two blinks of an eye to come up with an answer.

“I’ll be lying to protect you,”Gül says. “I’ll be lying because you’re children and I’m a grown-up.”

Even before Yılmaz and Saniye get there, Fuat has already poured himself a whisky and Coke.

“It beggars belief. While you were cleaning! Once a week the program’s on, and you go and break the aerial on a Saturday. Couldn’t it wait until Monday? Once a week we sit here nice and cozy together and they tell us what’s going on back home, once a week. Other women fall out onto the street while they’re cleaning the windows, and my wife has to go and destroy the aerial. You must have tugged pretty hard at it, and that’s what you call cleaning, is it? You shouldn’t be allowed anywhere near electrical devices, you shouldn’t even be allowed an iron. Once a week I watch a lovely slim presenter, not like my wife who’s so fat she rips the aerial off the telly. Why don’t you try dieting?”

It’s been like this all afternoon. Gül lets him moan as much as he likes, thinking up answers that go unsaid and smiling to herself because she knows Ceyda and Ceren are playing outside out of harm’s way. But after a while she’s had enough.

“It’s your fault I’m so fat.”

Fuat stares at her, amazed that she’s suddenly answering back. He’s even more amazed by her accusation, which he’s never heard before. Before he can come up with a response, Gül tells him: “It was you who came along with the pill, “Here you go, I’ve got something for you, so we don’t have to be careful anymore.” Without me going to see a doctor. It’s those pills that have made me swell up, those hormones or whatever they are. Who knows where you got them. And anyway, maybe you don’t like fat women, maybe you do want a slim blonde wife. But shall I tell you something for a change? I like men with hair on their heads, not baldies. You can’t always pick and choose what you get. You hear me? Men with a full head of hair!”

Fuat jerks his glass upwards, but he doesn’t pull back to hit her. Gül stands in front of him and looks him in the eye, and before the defeat she sees there turns into disaster, she leaves the room.

Later that evening, Yılmaz will say to Fuat: “That’s how I like it; you’re learning to drink now, my friend, just savoring it in peace, not getting louder with every sip you take.”

And Saniye will say to Gül: “It’s better, honest. The old one drank and beat me, and this one just drinks. God forbid, but if I ever marry again, perhaps the Lord will send me a husband who doesn’t do either. But who knows what flaws he’d have then? A man like Serter who’s lost his marbles isn’t what you’d want either. Your lahmacun is delicious by the way—may your hands always be healthy.”

Fuat will never say anything about Gül’s figure again. Nor Gül about his bald head. Women might pose in front of the mirror to inspect their new clothes or put on makeup, but it’s men who are made vulnerable by vanity.

*

Translators’ Note

Co-Translating Through the Comments Function: A Conversation Between Ayça Türkoğlu and Katy Derbyshire

Selim Özdoğan’s 52 Factory Lane is the second part of the Anatolian Blues trilogy, tracing out the life of a Turkish woman, Gül, who grows up in a small town and moves to Germany as a young mother. Having left her children behind to join her husband, she misses them every day until they can afford a home big enough for the family, on Factory Lane. The years of hard work will flow like water before her house in Turkey is built and Gül can return. Until then, there will be fireworks, young love, and the cassette tapes of the summer played on repeat. In these years, Gül will learn all kinds of longing: for her two daughters, for her father the blacksmith, for scents and colors and fruit. Yet imperceptibly, Factory Lane in cold, incomprehensible Germany becomes a different kind of home. A novel about how home is found in many places and yet still eludes us.

Below, Katy Derbyshire and Ayça Türkoğlu share some of the comments from the margins of the translation, and discuss the co-translation process.

I’d put this in quotation marks rather than italics, I think, because he’s actually saying it out loud. Fuat is a great sayer-out-loud.

This sounds a bit hip for Fuat. “Bring a child into the house?”

I don’t understand this so I’ve kind of guessed it. Is she saying “I had this idea and Fuat was mean about it,” or is she saying “Why did I have this bonkers idea?” Or something else?

I think your second suggestion is correct, i.e. she’s amazed at what a stupid thing she’s gone and done. So I think you need to adjust the English accordingly. But only the first sentence.

Not sure about “thickly hairy.” Perhaps “all the way up to the thick hair on his chest?”

Katy Derbyshire: How can two people translate one book? By tearing it down the middle and taking half each? By one of them doing a rough draft and the other polishing it up? I didn’t like either of those models. The first way, I suspect, wouldn’t make for a consistent and convincing voice. And the second seems pointlessly hierarchical and equally unpromising for creating a well-rounded work of literature. So for the first book in the Anatolian Blues trilogy, The Blacksmith’s Daughter, Ayça and I divided the novel into sections of three or four pages and translated alternating parts.

Nice one!!

I called it a chicken factory but I think it’s fine to vary slightly, and it doesn’t come up much.

Can this line start with a different word to avoid repeating the little para above?

Keep the German? Not sure, just a suggestion.

Heartbroken at this.

Yes!

Ayça Türkoğlu: We developed a shared style in the first few months of translating The Blacksmith’s Daughter, so when it came to translating 52 Factory Lane, we already had that under our belts. In this book, we get to hear more of the other characters’ voices—Fuat, in particular, really comes into his own. I always love translating Fuat because he’s so sharp-tongued. I know I can pull out all kinds of odd colloquialisms and rude turns of phrase and they’ll suit Fuat down to the ground. There’s much more humour in this book, I think, and it’s a challenge to make sure it lands properly.

Ooh, nice.

Hahahahaha, hilarious and gross in equal measure.

Yeah, eff you, you perv.

Fab!

“Off the books?” Or would she be all prim about it? Maybe “off the books” below?

Ha, I’ve slipped it in here!

Katy Derbyshire: I suspect (or I hope) one of the reasons why the humor works in the translation is because we egged each other on in our comments, which we inserted as we edited each section immediately after translating. A bit like a running commentary while you’re watching TV with a friend—or maybe like a Zoom chat section during a virtual event. Some of our comments were obviously about translation choices, but a good few were simply voicing our appreciation of the book. So there were lols and gasps and winces, extra jokes and shouts of encouragement to the characters, since both of us love them with a burning passion. And sometimes we shared childhood memories…

Tell me about it. Children who’d grown up in Turkey were always much smaller, spindlier than me. And my sister is basically an Amazon, so that blew their minds. You go into someone’s home and get given guest slippers, and they’d inevitably be a size 2 or something, and you’d be hanging off the back of them.

I remember my nanna saying something similar when my cousin said she was getting picked on for having a Black boyfriend.

Happy to live in London and be free of the tiny tomato puree tube tyranny of my childhood.

Ha! I’m stuck with tubes. Do we want to make this tomato puree, by the way?

Just change this to “she needs a permit” even though it’s not what it means?

Yes, good thinking.

Ayça Türkoğlu: Working together also meant an extra person to puzzle over parts of the text with. There are a fair number of instances where you’re not quite sure what the author is trying to say, in a way that goes beyond comprehension of the words on the page. You might ask the author, but they might have already forgotten why they wrote what they did. Working together gave each of us that extra boost when it came to deciphering a slightly corny joke (“Squeaksqueaksqueak?” Come on), navigating cultural aspects that might otherwise be lost, and daring to move away from the meaning of the text on the page.

I always assume this is way cruder an expression than it seems to be. I can’t decide if it’s something Gül would actually say.

Sounds crude to me! But then so does “bugger.”. Not sure…

I’ve had a bit of a look and I say we go with bloomers, but let’s ask Selim too, just in case. I’m not as au fait with Black Sea lingerie as I’d like to be.

I might have gone overboard here.

I think it’s great but I thought at first it was Alper who was meant, so maybe change “he” to “it?”

Hmm, what do we do here about the difference in attitude towards children and fireworks between the UK and Germany? Almost everyone I know here gives kids fireworks on NYE. Lots of drunk men instructing kids on how to light rockets.

Katy Derbyshire: In the case of this book, there are two cultures involved that Anglophone readers might not be familiar with—Turkish and German. And we wanted it to be clear to readers when the Turkish characters were doing things that seem perfectly normal in a German context—like casually allowing children to play with fireworks —and when they might stand out. While footnotes can be a thing of beauty, we never considered them for this book, so there were times when we made cautious additions. In the case of the fireworks we inserted a gentle “like everyone else in the town” to the description of the family’s New Year’s Eve party.

This is just a placeholder for “Arbeit ist Arbeit…” What do you think—translate it literally (for a laugh), do something lame and explain-y (like this placeholder), or can you think of a corresponding English phrase?

Hmmm. “Work comes first here?” “You know what the Germans say: Work is work, schnapps is schnapps?”

Ah so it’s bread and butter!

I misread this as “turns up after work.” Maybe “after the morning bell” or something? Don’t know if they’d have a bell, just thinking of that film We Want Sex/Made in Dagenham.

This is hilarious and fab, but I wonder if custard just seems a bit out of place culturally. Not that we’ve been particularly fastidious about this kind of thing in the past. Up to you.

This needs work, but I’m sure this bit (“Es geht nicht nach dem Geldbeutel, es geht nach der Reihe”) should rhyme in Turkish.

Ayça Türkoğlu: In this book, as in The Blacksmith’s Daughter, we put more Turkish back into the text. This included changes like recreating sayings that rhymed, as in the example above, and shifting terms of address into Turkish, where they might have been English in The Blacksmith’s Daughter. Sometimes we aimed for specificity, at others, we were more relaxed. This free and easy approach felt right; we didn’t get caught up in aiming for rigid consistency, but let ourselves be carried along and moved by the story, choosing what felt right at the time. I thought The Blacksmith’s Daughter was my favorite book in the trilogy, but now I think it’s this one, or perhaps the next…

It’s “Gott möge sie nicht bestrafen” but I feel like this has a similar vibe? Maybe? Like the way that old women try to pretend they’re not being mean by saying things like “She’s not much to look at, bless her.”

Ürks! Is this awful?

Peak Fuat.

Not sure about this. He says Fremdenfeindlichkeit rather than racism, but would he say xenophobia? It’s such a mouthful. The F-word was used much more a few decades ago; now it’s more of a euphemism. What are your thoughts?

Yeah, that’s tricky. I’d be inclined to go with ‘racism’, just because it’s shorter and really means something. Xenophobia feels more like theory than real-life chat.

This is Gül, right?

–Berlin and London, September 2021

_________________________________

Excerpted from 52 Factory Lane by Selim Özdogan, translated by Ayça Türkoğlu and Katy Derbyshire. Reprinted with permission of the publisher V&Q Books. Copyright (c) 2022.